The world is complex. Yet most of our popular stories and ideologies tend not to reflect this complexity. Which is to say that our stories and ideologies, and by extension we, tend to have insufficiently nuanced perspectives on the world.

Indeed, falling into a simple narrative through which we can easily categorize and make sense of the world — e.g. “it’s all God’s will”; “it’s all class struggle”; “it’s all the muslims’ fault”; “it’s all a matter of interwoven forms of oppression” — is a natural and extremely powerful human temptation. And something social constructivists get very right is that this narrative, the lens through which we see the world, influences our experience of the world to an extent that is difficult to appreciate.

So much more important, then, that we suspend our urge to embrace simplistic narratives to (mis)understand the world through. In order to navigate wisely in the world, we need to have views that reflect its true complexity — not views that merely satisfy our need for simplicity (and social signaling; more on this below). For although simplicity can be efficient, and to some extent is necessary, it can also, when too much too relevant detail is left out, be terribly costly. And relative to the needs of our time, I think most of us naturally err on the side of being expensively unnuanced, painting a picture of the world with far too few colors.

Thus, the straightforward remedy I shall propose and argue for here is that we need to control for this. We need to make a conscious effort to gain more nuanced perspectives. This is necessary as a general matter, I believe, if we are to be balanced and well-considered individuals who steer clear of self-imposed delusions. Yet it is also necessary for our time in particular. More specifically, it is essential in addressing the crisis that human conversation seems to be facing in the Western world today — a crisis that largely seems the result of an insufficient amount of nuance in our perspectives.

Some Remarks on Human Nature

There are certain facts about the human condition that we need to put on the table and contend with. These are facts about our limits and fallibility that should give us all pause about what we think we know — both about the world in general and about ourselves in particular.

For one, we have a whole host of well-documented cognitive biases. There are far too many for me to list them all here, yet some of the most important ones are: confirmation bias (the tendency of our minds to search for, interpret, and recall information that confirms our pre-existing beliefs); wishful thinking (our tendency to believe what we wish were true); and overconfidence bias (our tendency to have excessive confidence in our own beliefs — in one study, people who reported to be 100 percent certain about their answer to a question were correct less than 85 percent of the time). And while we can probably all recognize these pitfalls in other people, it is much more difficult to realize and admit that they afflict ourselves as well. In fact, our reluctance to realize this is itself a well-documented bias, known as the bias blindspot.

Beyond acknowledging that we have fallible minds, it is also helpful to understand the deeper context that has given rise to much of this fallibility, and which continues to fuel it, namely our social context — both the social context of our evolutionary history as well as that of our present condition. We humans are deeply social creatures, which shows at every level of our design, including the level of our belief formation. And we need to be acutely aware of this if we are to form reasonable beliefs with minimal amounts of self-deception.

Yet not only are we social creatures, we are also, by nature, deeply tribal creatures. As psychologist Henri Tajfel showed, one need only assign one group of randomly selected people the letter “A” and another randomly selected group the letter “B” in order for a surprisingly strong in-group favoritism to emerge. This method for studying human behavior is known as the minimal group paradigm, and it shows something about us that history should already have taught us a long time ago: that human tribalism is like gasoline just waiting for a little spark to be ignited.

Our social and tribal nature has implications for how we act and what we believe. It is, for instance, largely what explains the phenomenon of groupthink, which is when our natural tendency toward (in-)group conformity leads to a lack of dissenting viewpoints among individuals in a given group, which in turn leads to poor decisions by these individuals.

Indeed, our beliefs about the world are far more socially influenced than we tend to realize, not just in that we get our views from others around us, but also in that we often believe things in order to signal to others that we possess certain desirable traits, or to signal that we are loyal to them. This latter way of thinking about our beliefs is quite at odds with how we prefer to think about ourselves, yet the evidence for this unflattering view is difficult to deny at this point.

As authors Robin Hanson and Kevin Simler argue in their recent book The Elephant in the Brain, we humans are strategically self-deceived about our own motives, including when it comes to what motivates our beliefs. Beliefs, they argue, serve more functions than just the function of keeping track of what is true of the world. For while beliefs surely do serve this practical function, they also often serve a very different, very social function, namely to show others what kind of person we are and what kind of groups we identify with. This makes beliefs much like clothes, which have the practical function of keeping us warm while, for most of us, also serving the function of signaling our tastes and group affiliations. One of Hanson and Simler’s main points is that we are not consciously aware that our beliefs have these distinct functions, and that there is an evolutionary reason for this: if we realized (clearly) that we believe certain things for social reasons, and if we realized that we display our beliefs with overconfidence, we would be much less convincing to those we are trying to convince and impress.

Practical Implications of Our Nature

The preceding survey of the pitfalls and fallibilities of our minds is far from exhaustive, of course, but it shall suffice for our purposes. The bottom line is that we are creatures who want to see our pre-existing beliefs confirmed, and who tend to display excessive confidence in these beliefs. We do this in a social context, and many of the beliefs we hold serve social rather than epistemic functions, which include the tribal function of showing others how loyal we are to certain groups, as well as how worthy we are as friends and mates. In other words, we have a natural pull to impress our peers, not just with our behavior but also with our beliefs. And for socially strategic reasons, we are quite blind to the fact that we do this.

So what, then, is the upshot of all of this? A general implication, I submit, is that we have a lot to control for if we aspire to have reasonable beliefs, and our own lazy mind, with all its blindspots and craving for simple comfort, is not our friend in this endeavor. The fact that we are naturally biased and tendentious gives us reason to doubt our own beliefs and motives. More than that, it gives us reason to actively seek out the counter-perspectives and nuance that our confirmation bias so persistently struggles to keep us from accessing.

Reducing Our Biases

If we are to form accurate and nuanced perspectives, it seems helpful to cultivate an awareness of our biases, and to make an active effort to curb them.

Countering Confirmation Bias

To counteract our confirmation bias, it is critical to seek out viewpoints and arguments that challenge our pre-existing beliefs. We all cherry-pick data a little bit here and there in favor of our own position, and so by hearing from people with opposing views, and by examining their cherry-picked data and their particular emphases and interpretations, we will, in the aggregate, tend to get a more balanced picture of the issues at hand.

Important in this respect is that we engage with these other views in a charitable way, by assuming good faith on behalf of the proponents of any position; by trying to understand their view as well as possible; and by then engaging with the strongest possible version of that position — i.e. the steelman rather than the strawman version of it.

Countering Wishful Thinking

Our propensity for wishful thinking should make us skeptical of beliefs that are convenient and which match up with what we want to be true. If we want there to be a God, and we believe that there is one, then this should make us at least a little skeptical of this convenient belief. By extension, our attraction toward the wishful also suggests that we should pay more attention to information and arguments that are inconvenient or otherwise contrary to what we wish were true. Do we believe that the adoption of a vegan lifestyle would be highly inconvenient for us personally? Then we should probably expect to be more than a little biased against any argument in its favor; and if we suspect that the argument has merit, we will likely be inclined to ignore it altogether rather than giving it a fair hearing.

Countering Overconfidence Bias

When it comes to reducing our overconfidence bias, intellectual humility is a key virtue. That is, to admit and speak as though we have a limited and fallible perspective on things. In this respect, it also helps to be aware of the social motives that might be driving our overconfidence much of the time, such as the motive of convincing others or to signal our traits and loyalties. These social functions of confidence give us reason to update away from bravado and toward being more measured.

Countering In-Group Conformity

As hinted above, our beliefs are subject to in-group favoritism, which highlights the importance of being (especially) skeptical of the beliefs we share with groups that we affiliate closely with, while being extra charitable toward the beliefs held by the notional out-group. Likewise, it is worth being aware that our minds often paint the out-group in an unfairly unfavorable light, viewing them as much less sincere and well-intentioned than they actually are.

Thinking in Degrees of Certainty

Many of us have a tendency to express our views in a very binary, 0-or-1 fashion. We tend to be either clearly for something or clearly against it, be it abortion, efforts to prevent climate change, or universal health care. And it seems that what we express outwardly is generally much more absolutist, i.e. more purely 0 or 1, than what happens inwardly — underneath our conscious awareness — where there is probably more conflicting data than what we are aware of and allow ourselves to admit.

I have observed this pattern in conversations: people will argue strongly for a given position that they continue to insist on until, quite suddenly, they say that they accept the opposite conclusion. In terms of their outward behavior, they went from 0 to 1 quite rapidly, although it seems likely that the process that took place underneath the hood was much more continuous — a more gradual move from 0 to 1.

An extreme example of similar behavior found in recent events is that of Omarosa Manigault Newman, who was the Director of African-American Outreach for Donald Trump’s presidential campaign in 2016. She went from describing Trump in adulating terms, calling him “a trailblazer on women’s issues”, to being strongly against him and calling him a racist and a misogynist. It seems unlikely that this shift was based purely on evidence she encountered after she made her adulating statements. There probably was a lot of information in her brain that contradicted those flattering statements, but which she ignored and suppressed. And the reason why is quite obvious: she had a political motive. She needed to broadcast the message that Trump was a good person to further a campaign and to further her own career tied to this campaign. It was about signaling first, not truth-tracking.

The important thing to realize, of course, is that this applies to all of us. We are all inclined to be more like a politician than a scientist in many situations. In particular, we are all inclined to believe and express either a pure 0 or a pure 1 for social reasons.

Fortunately, there is a corrective for our tendency toward 0-or-1 thinking, which is to think in terms of credences along a continuum, ranging from 0 to 1. Thinking in these terms can help make our expressed beliefs more refined and more faithful to the potentially contradicting information found in our brains. Additionally, such graded thinking may help subvert the tribal aspect of our either-or thinking, by moving us away from a framework of binary polarity and instead placing us all in the same boat: the boat of degrees of certainty, in which the only thing that differs between us is our level of certainty in any given claim.

Such an honest, more detailed description of one’s beliefs is not good for keeping groups divided by different beliefs. Indeed, it is good for the exact opposite: it helps us move toward a more open and sincere conversation about what we in fact believe and why, regardless of our group affiliations.

Different Perspectives Can Be Equally True

There are two common definitions of the term “perspective” that are quite different, yet closely related. One is “a mental outlook/point of view”, while the other is “the art of representing three-dimensional objects on a two-dimensional surface”. These definitions are related in that the latter can be viewed as a metaphor for the former: our particular perspective, the representation of the world we call our point of view, is in a sense a limited representation of a more complex, multi-dimensional reality — a representation that is bound to leave out a lot of information about the world at large. The best we can do, then, is to try to paint the canvas of our mind so as to make it as rich and informative as possible about the complex and many-faceted world we inhabit.

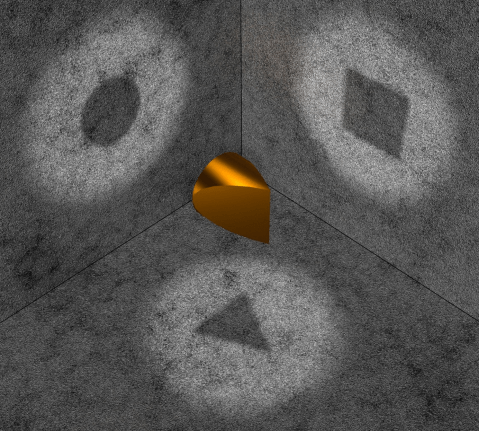

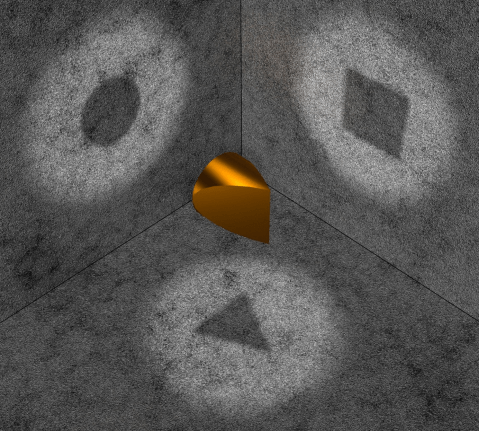

An important point for us to realize in our quest for more balanced and nuanced views, as well as for the betterment of human conversation, is that seemingly conflicting reports of different perspectives on the same underlying reality can all be true, as hinted by the following illustration:

The same object can have different reflections when viewed from different angles. Similarly, the same events can be viewed very differently by different people who each have their own unique dispositions and prior experiences. And these different views can all be true; John really does see X when he looks at this event, while Jane really does see Y. And, like the different reflections shown above, X and Y need not be incompatible. (A similar sentiment is reflected in the Jain doctrine of Anekantavada.)

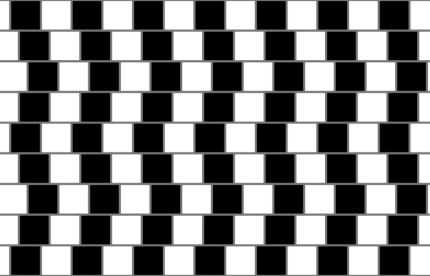

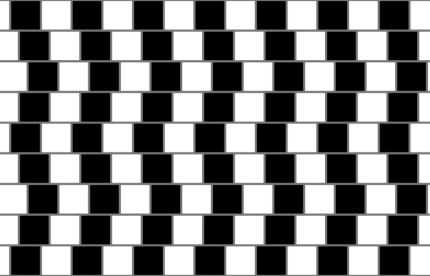

And even when someone does get something wrong, they may nonetheless still be truthfully reporting the appearance of the world as it is revealed to them. For example, to many of us, it really does seem as though the lines in the following picture are not parallel, although they in fact are:

This is merely to state the obvious point that it is possible, indeed quite common, to be perfectly honest and wrong at the same time, which is worth keeping in mind when we engage with people whom we think are obviously wrong; they usually think that they are right, and that we are obviously wrong — and perhaps even dishonest.

Another important point the visual illusion above hints at is that we should be careful not to confuse external reality with our representation of it. Our conscious experience of the external world is not, obviously, the external world itself. And yet we tend to speak as though it were.

This is no doubt an evolutionarily adaptive illusion, but it is an illusion nonetheless. All we ever inhabit is, in the words of David Pearce, our own world-simulation, a world of conscious experience residing in our head. And given that we all find ourselves stuck in — or indeed as — such separate, albeit mutually communicating bubbles, it is not so strange that we can have so many disagreements about what reality is like. All we have to go on is our own private, phenomenal cartoon model of each other and the world at large; a cartoon model that may get many things right, but which is also sure to miss a lot of important facts and phenomena.

Framing Shapes Our Perspective

From the vantage point of our respective world-simulations, we each interpret information from the external world with our own unique framing. And this framing partly determines how we will experience what we observe, as demonstrated by the following illustration, where one can change one’s framing so as to either see a duck or a rabbit:

Sometimes, as in the example above, our framing is readily alterable. In other cases, however, it can be more difficult to just switch our framing, as when it comes to how people with different life experiences will naturally interpret the same scenario. After all, we each experience the world in different ways, due to our unique biological dispositions and life experiences. And while differing outlooks are not necessarily incompatible, it can still be challenging to achieve mutual understanding between perspectives that are shaped by very different experiences and cultural backgrounds.

Acknowledging Many Perspectives Is Not a Denial of Truth

None of the above implies the relativistic claim that there are no truths. On the contrary, the above implies that it is itself a truth that different individuals can have different perspectives and experiences in reaction to the same external reality, and that it is possible for such differing perspectives to all have merit, even if they appear to be in tension with each other. This middle-position of rejecting both the claim that there is only one valid perspective and the claim that there are no truths is, I submit, the only reasonable one on offer.

The fact that there can be merit in a plurality of perspectives implies that, beyond conceiving of our credences along a continuum ranging from 0 to 1, we also need to think in terms of a diversity of continua in a more general sense if we are to gain a nuanced understanding that does justice to reality, including the people around us with whom we interact. More than just thinking in terms of shades of grey found in between the two endpoints of black and white, we need to think in terms of many different shades of many different colors.

At the same time, it is also important to acknowledge the limits of our understanding of other minds and of experiences that we have not had. This does not amount to some obscure claim about how we each have our own, wholly incommensurable experiences, and hence that mutual understanding between individuals with different backgrounds is impossible. Rather, it is simply to acknowledge that psychological diversity is real, which implies that we should be careful to avoid the so-called typical mind fallacy (i.e. the mistake of thinking that other minds work just like our own). More than that, admitting the limits of our understanding of others’ experiences is to acknowledge that at least some experiences just cannot be conveyed faithfully with words alone to those who have not had them. For example, most of us have never tried experiencing extreme forms of suffering, such as the experience of being burned alive, and hence we are largely ignorant about the nature of such experiences.

However, this realization that we do not know what certain experiences are like is itself an important insight that expands and advances our outlook. For it at least helps us realize that our own understanding, as well as the variety of experiences that we are familiar with, are quite limited. With this realization in mind, we can look upon a state of absolute horror and admit that we have virtually no understanding of just how bad it is, which I submit represents a significantly greater level of understanding than does beholding such a state of horror without acknowledging of our lack of comprehension. The realization that we are ignorant itself constitutes knowledge of sorts — the kind of knowledge that makes us rightfully humble.

Grains of Truth in Different Perspectives

Even when two different perspectives are in conflict with each other, this does not imply that they are both entirely wrong, as there can still be significant grains of truth in both of them. Most of today’s popular narratives make a wide range of claims and arguments, and even if not all of these stand up to scrutiny, many of them arguably do. And part of being charitable is to seek out such grains of truth in positions that one does not agree with. This can also help give us a better sense of which realities and plausible claims might motivate people to support (what we consider) misguided views, and thus help advance mutual understanding.

As mentioned earlier, it is possible for different perspectives to support what seem to be very different positions on the same subject without necessarily being wrong; if they have different lenses, looking in different directions. Indeed, different perspectives on the same issue are often merely the result of different emphases that each focus on certain framings and sets of data rather than others. This is, I believe, a common pattern in human conversation: when different views on the same subject are all mostly true, yet where each of them merely constitute a small piece of the full picture — a pattern that further highlights the importance of seeking out different perspectives.

Having made a general case for nuance, let us now turn our gaze toward our time in particular, and why it is especially important to actively seek to be nuanced and charitable today.

Our Time Is Different: The Age of Screen Communication

Every period in history likely sees itself as uniquely special. Yet in terms of how humanity communicates, it appears that our time indeed is a highly unique one. Never before in history has human communication been so screen-based as it is today, which has significant implications for how and what we communicate.

Our brain seems to process communication through a screen in a very different way than it processes face-to-face communication. Writing a message in a Facebook group consisting of a thousand people does not, for most of us, feel remotely the same as delivering an equivalent speech in front of a live audience of a thousand people. And a similar discrepancy between the two forms of communication is found when we interact with just a single person. This is no wonder. After all, communication through a screen consists of a string of black and white symbols. Face-to-face interaction, in contrast, is composed of multiple streams of information; we read off important cues from a person’s face and posture, as well as from the tone and pace of their voice.

All this information provides a much more comprehensive — one might say more nuanced — picture of the state of mind of the person that we are interacting with. We get the verbal content of the conversation (as we would through a screen), plus a ton of information about the emotional state of the person who communicates. And beyond being informative, this information also serves the purpose of making the other person relatable. It makes the reality of their individuality and emotions almost impossible to deny, which is much less true when we communicate through a screen.

Indeed, it is as though these two forms of communication activate quite different sets of brain circuits — not only in that we communicate via a much broader bandwidth and likely see each other as more relatable when we communicate face-to-face, but also in that face-to-face communication naturally motivates us to be civil and agreeable. When we are in the direct physical presence of someone else, we have a strong interest in keeping things civil enough to allow our co-existence in the same physical space. Yet when we interact through a screen, this is no longer a necessity.

These differences between the two forms of communication give us reason to try to be especially nuanced when communicating through screens, not least because written communication through a screen makes it easier than ever before to paint the out-group antagonists whom we interact with in an unreasonably unfavorable light.

Indeed, our modern means of communication arguably make it easier than ever before to not interact with the out-group at all, as the internet has made it possible for us to diverge into our own respective echo chambers to an extent not possible in the past. It is thus easy to end up in communities in which we continuously echo data that supports our own narrative, which ultimately gives us a one-sided and distorted picture of reality. And while it may also be easier than ever before to find counter-perspectives if we were to look for them, this is of little use if we mostly find ourselves collectively indulging in our own in-group confirmation bias, as we often do. For instance, feminists may find themselves mostly informing each other about how women are being discriminated against, while men’s rights activists may disproportionally share and discuss ways in which men are being discriminated against. And so by joining only one of these communities, one is likely to end up with a skewed and insufficiently nuanced picture of reality.

With all the information we have reviewed thus far in mind, let us now turn to some concrete examples of heated issues that divide people today, and where more nuanced perspectives and a greater commitment to being charitable seem desperately needed. I should note that, given the brevity of the following remarks, what I write here on these issues is itself bound to fail to express a highly nuanced perspective, as that would require a longer treatment. Nonetheless, the following brief remarks will at least gesture at some ways in which we can try to be more nuanced about these topics.

Sex Discrimination

As hinted above, there are different groups that seem to tell very different stories about the state of sex discrimination in our world today. On the one hand, there are feminists who seem to argue that women generally face much more discrimination than men, and on the other, there are men’s rights activists who seem to argue that men are, at least in some parts of the world, generally the more discriminated sex. These two claims surely cannot both be right, can they?

If one were to define sex discrimination in terms of some single general measure, a “General Discrimination Factor”, then they could not both be right. Yet if one instead talks about concrete forms of discrimination, it is entirely possible, and indeed clearly the case, that women face more discrimination than men in some respects, while men face more discrimination in other respects. And it is arguably also more fruitful to talk about such concrete cases than it is to talk about discrimination “in general”. (In response to those who think that it is obvious that women face more discrimination in every domain, I would recommend watching the documentary The Red Pill, and for a more academic treatment, reading David Benatar’s The Second Sexism.)

For example, it is a well-known fact that women have, historically, been granted the right to vote much later than men have, which undeniably constitutes a severe form of discrimination against women. Similarly, women have also historically been denied the right to pursue a formal education, and they still are in many parts of the world. In general, women have been denied many of the opportunities that men have had, including access to professions in which they were clearly more than competent to contribute. These are all undeniable facts about undeniably serious forms of discrimination.

However, tempting as it may be to infer, none of this implies that men have not also faced severe discrimination in the past, nor that they avoid such discrimination today. For example, it is generally only men who have been subject to military conscription, i.e. forced duty to enlist in the military. Historically, as well as today, men have — in vastly disproportional numbers — been forced by law to join the military and to go to war, often without returning. (As a side note, it is worth noting that many feminists have criticized conscription.)

Thus, on a global level, it is true to say that, historically as well as today, women have generally faced more discrimination in terms of their rights to vote and to pursue an education, as well as in their professional opportunities, while men have faced more discrimination in terms of state-enforced duties.

Different forms of discrimination against men and women are also present at various other levels. For example, in one study where the same job application was sent to different scientists, and where half of the applications had a female name on them, the other half a male name, the “female applicants” were generally rated as less competent, and the scientists were willing to pay the “male applicants” more than 14 percent more.

The same general pattern seems reported by those who have conducted a controlled experiment in being a man and a woman from the “inside”, namely from transgender men (those who have transitioned from being a woman to being a man). Many of these men report being viewed as more competent after their transition, as well as being listened to more and interrupted less. This fits with the finding that both men and women seem to interrupt women more than they interrupt men.

At the same time, many of these transgender men also report that people seem to care less about them now that they are men. As one transgender man wrote about the change in his experience:

What continues to strike me is the significant reduction in friendliness and kindness now extended to me in public spaces. It now feels as though I am on my own: No one, outside of family and close friends, is paying any attention to my well-being.

Such anecdotal reports seem in line with the finding that both men and women show more aggression toward men than they do toward women, as well as with recent research led by social psychologist Tania Reynolds, which among other things found that:

… female harm or disadvantage evoked more sympathy and outrage and was perceived as more unfair than equivalent male harm or disadvantage. Participants more strongly blamed men for their own disadvantages, were more supportive of policies that favored women, and donated more to a female-only (vs male-only) homeless shelter. Female participants showed a stronger in-group bias, perceiving women’s harm as more problematic and more strongly endorsed policies that favored women.

It thus seems that men and women are generally discriminated against in different ways. And it is worth noting that these different forms of discrimination are probably in part the natural products of our evolutionary history rather than some deliberate, premeditated conspiracy (which is obviously not to say that they are ethically justified).

Yet deliberation and premeditation is exactly what is required if we are to step beyond such discrimination. More generally, what seems required is that we get a clearer view of the ways in which women and men face discrimination, and that we then take active steps toward remedying these problems — something that is only possible if we allow ourselves enough of a nuanced perspective to admit that both women and men are subject to serious discrimination.

Intersectionality

It seems that many progressives are inspired by the theoretical framework called intersectionality, according to which we should seek to understand many aspects of the modern human condition in terms of interlocking forms of power, oppression, and privilege. One problem with relying on this framework is that it can easily become like only seeing nails when all one has is a hammer. If one insists on understanding the world predominantly in terms of oppression and social privilege, one risks overemphasizing its relevance in many cases — and, by extension, to underemphasize the importance of other factors.

As with most popular ideas, there is no doubt a significant grain of truth in some of what intersectional theory talks about, such as the fact that discrimination is a very real phenomenon, that privilege is too, and that both of these phenomena can compound. Yet the narrow focus on social explanations and versions of these phenomena means that intersectional theory misses a lot about the nature of discrimination and privilege. For example, some people are privileged to be born with genes that predispose them to be significantly happier than average, while others have genes that dispose them to have chronic depression. Such two people may be of the same race, gender, and sexuality, and they may be equally able-bodied. Yet such two people will most likely have very different opportunities and qualities of life. A similar thing can be said about genetic differences that predispose individuals to have a higher or lower IQ, and about genetic differences that make people more or less physically attractive.

Intersectional theory seems to have very little to say about such cases, even as these genetic factors seem able to impact opportunities and quality of life to a similar degree as do discrimination and social exclusion. Indeed, it seems that intersectional theory actively ignores, or at the very least underplays, the relevance of such factors — what may be called biological privileges — perhaps because they go against the tacit assumption that inequity must be attributable to oppressive agents or social systems in some way, as opposed to just being the default outcome that one should expect to find in an apathetic universe.

It seems that intersectional theory significantly underestimates the importance of biology in general, which is, of course, by no means a mistake that is unique to intersectional theory. And it is quite understandable how such an underestimation can occur. For the truth is that many human traits, including those of personality and intelligence, are strongly influenced by both genetic and environmental factors. Indeed, around 40-60 percent of the variance in such traits tends to be explained by genetics, and, consequently, the amount of variance explained by the environment lies roughly in this range as well. This means that, with respect to these traits, it is both true to say that cultural factors are extremely significant, and that biological factors are extremely significant. The mistake that many seem to make, including many proponents of intersectionality, is to think that one of these truths rules out the other.

More generally, a case can be made that intersectional theory greatly overemphasizes group membership and identities in its analyses of societal problems. As Brian Tomasik notes:

… I suspect it’s tempting for our tribalistic primate brains to overemphasize identity membership and us-vs.-them thinking when examining social ills, rather than just focusing on helping people in general with whatever problems they have. For example, I suspect that one of the best ways to help racial minorities in the USA is to reduce poverty (such as through, say, universal health insurance), rather than exploring ever more intricate nuances of social-justice theory.

A final critique I would direct at mainstream intersectional theory is that, despite its strong focus on unjustified discrimination, it nonetheless generally fails to acknowledge and examine what is, I have argued, the greatest, most pervasive, and most harmful form of discrimination that exists today, namely speciesism — the unjustified discrimination against individuals based on their species membership. This renders mainstream versions of intersectionality a glaring failure as a theory of discrimination against vulnerable individuals.

Political Correctness

Another controversial issue closely related to intersectionality is that of political correctness. What do we mean by political correctness? The answer is actually not straightforward, since the term has a rather complex history throughout which it has had many different meanings. One sense of the term refers simply to conduct and speech that embodies fairness and common decency toward others, especially in a way that avoids offending particular groups of people. In this sense of the term, political correctness is, among other things, about not referring to people with ethnic or homophobic slurs. A more recent sense of the term, in contrast, refers to instances where such a commitment to not offend people has been taken too far (in the eyes of those who use the term), which is arguably the sense in which it is most commonly used today.

This then leads us to what seems the main point of contention when it comes to political correctness, namely: what is too far? What does the optimal level of decency entail? The only sensible answer, I believe, will have to be a nuanced one found between the two extremes of “nothing is too offensive” and “everything is too offensive”.

Some seem to approach this subject with the rather unnuanced attitude that feelings of being offended do not matter in any way whatsoever. Yet this view seems difficult to maintain, at least if one is called a pejorative name in an unjoking manner oneself. For most people, such name-calling is likely to hurt — indeed, it may hurt quite a lot. And significant amounts of hurt and unpleasantness do, I submit, matter. A universe with fewer, less intense feelings of offense is, other things being equal, better than a universe with more, more intense feelings of offense.

Yet the words “other things being equal” should not be missed here. For the truth is that there can be, indeed there clearly is, a tension between 1) risking to offend people, and 2) talking freely and honestly about the realities of life. And it is not clear what the optimal balance is.

What is quite clear, I would argue, is that if we cannot talk in an unrestricted way about what matters most in life, then we have gone too far. In particular, if we cannot draw distinctions between different kinds of discrimination and forms of suffering, and if we are not allowed to weigh these ills against each other to assess which are most urgent, then we have gone too far. If we deny ourselves a clear sense of proportion with respect to the problems of the world, we end up undermining our ability to sensibly prioritize our limited resources in a world that urgently demands reasonable prioritization. This is too high a price to pay to avoid the risk of offending people.

Politics and Making the World a Better Place

The subjects of politics and “how to make the world a better place” more generally are both subjects on which people tend to have strong convictions, limited nuance, and powerful incentives to signal group loyalties. Indeed, they are about as good examples as any of subjects where it is important to be charitable and to actively seek out nuance, as well as to acknowledge our own biased nature.

A significant step we can take toward thinking more clearly about these matters is to adopt the aforementioned virtue of thinking in terms of continuous credences. Having a “merely” high credence in any given political ideology, principle, or policy is likely more conducive to honest and constructive conversations than is a position of perfect conviction.

If nothing else, the fact that the world is so complex implies that there is considerable uncertainty about what the consequences of our actions will be. In many cases, we simply cannot know with great certainty which policy or candidate is ultimately going to be best (relative to any set of plausible values). This suggests that our strong convictions about how a given political candidate or policy is all bad, and about how immeasurably greater the alternatives would be, are likely often overstated. More broadly, it implies that our estimates regarding which actions are best to take, in the realm of politics in particular and with respect to improving the world in general, should probably be more measured and humble than they tend to be.

A related pitfall worth avoiding is that of believing a single political candidate or policy to have purely good or purely bad effects; such an outcome seems extraordinarily unlikely. Similarly, it is worth steering clear of the tendency to look to a single intellectual for the answers to all important questions. The truth is that we all have blindspots and false beliefs. Indeed, no single person can read and reflect widely and deeply enough to be an expert on everything of importance. Expertise requires specialization, which means that we must look to different experts if we are to find expert views on a wide range of topics. In other words, the quest for a more complete and nuanced outlook requires us to engage with many different thinkers spanning a wide range of disciplines.

Can We Have Too Much Nuance?

In a piece that argues for the virtues of being nuanced, it seems worth asking whether I am being too one-sided. Might I not be overstating the case in its favor, and should I not be a bit more nuanced about the utility of nuance itself? Indeed, might we not be able to have too much nuance in some cases?

I would be the first to admit that we probably can have too much nuance in many cases. I will grant that in situations that call for quick action, and where there is not much time to build a nuanced perspective, it may often be better to act on one’s limited understanding rather than a more nuanced, yet harder-won picture. However, at the level of our public conversations, this is not typically the case. In that context, we usually do have time to build a more nuanced picture, and we are rarely required to act promptly. Indeed, we are rarely required to act at all, and perhaps it is generally better to abstain from expressing our views on a given hot topic if we have not made much of an effort to understand it.

One could perhaps attempt to make a case against nuance with reference to examples where near-equal weight is granted to all considerations and perspectives — reasonable and less reasonable ones alike. This, one may argue, is a bad thing, and surely demonstrates that there is such a thing as too much nuance. Yet while I would agree that weighing arguments blindly and undiscerningly is unreasonable, I would not consider this an example of too much nuance as such. For being nuanced does not mean giving equal weight to all arguments regardless of their plausibility. Instead, what it requires is that we at least consider a wide range of arguments, and that we acknowledge whatever grains of truth that these arguments might have, but without overstating their degree of truth or plausibility.

Another objection one may be tempted to raise against being nuanced and charitable is that it implies that we should be submissive and over-accommodating. This does not follow, however. To say that we have reason to be nuanced and charitable is not to say that we cannot be firm in our convictions when such firmness is justified, much less that we should ever tolerate disrespect or unfair treatment. We have no obligation to indulge bullies and intimidators, and if someone repeatedly fails to act in a respectful, good-faith manner, we have every right to remove ourselves from them. After all, the maxim “assume the other person is acting in good faith” in no way prevents us from updating this assumption as soon as we encounter evidence that contradicts it. And to assert one’s boundaries and self-respect in light of such updating is perfectly consistent with a commitment to being charitable.

A more plausible critique against being nuanced is that it might sometimes be strategically unwise, and that advocating one’s ideas in a decidedly unnuanced and polemic manner might be better for achieving certain aims. I think this may well be true. Yet I think there are also good reasons to think that this will rarely be the optimal strategy when engaging in public conversations, especially in the long run. First of all, we should acknowledge that, even if we were to grant that an unnuanced style of communication is superior in some situations, it still seems advantageous to possess a nuanced understanding of the arguments against one’s own views. If nothing else, such an understanding would seem to make one better able to rebut these arguments, regardless of whether one then does so in a nuanced way or not.

In addition to this reason to acquire a nuanced understanding, there are also good reasons to express such an understanding, as well as to treat counter-arguments in a fair and measured way. One reason is the possibility that we might ourselves be wrong, which means that, if we want an honest conversation through which we can make our beliefs converge toward what is most reasonable, then we ourselves also have an interest in seeing the best and most unbiased arguments for and against different views. And hence we ourselves have an interest in moderating our own bravado and confirmation bias that actively keep us from evaluating our pre-existing beliefs as impartially as we ideally should.

Beyond that, there are reasons to believe that people will be more receptive to one’s arguments if one communicates them in a way that demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of relevant counter-arguments, and which lays out opposing views as strongly as possible. This will likely lead people to conclude that one’s perspective is at least built in the context of a sophisticated understanding, which might be read as an honest signal that this perspective may be worth listening to.

Finally, one may object that some subjects just do not call for any nuance whatsoever. For example, should we be nuanced about the Holocaust? This is a reasonable point. Yet even here, I would argue that nuance is still important, in various ways. For one, if we do not have a sufficiently nuanced understanding of the Holocaust, we risk failing to learn from it. For example, to simply believe that the Germans were evil would appear the dangerous thing, as opposed to realizing that what happened was the result of primitive tendencies that we all share, as well as the result of a set of ideas which had a strong appeal to the German people for various reasons — reasons that are worth understanding.

This is all descriptive, however, and so none of it implies taking a particularly nuanced stance on the ethical status of the Holocaust. Yet even in this respect, a fearless search for nuance and perspective can still be of great importance. In terms of the moral status of historical events, for instance, we should have enough perspective to realize that the Holocaust, although it was the greatest mass killing of humans in history, was by no means the only one; and hence that its ethical status is arguably not qualitatively unique compared to other similar events of the past. Beyond that, we should admit that the Holocaust is not, sadly, the greatest atrocity imaginable, neither in terms of the number of victims it had, nor in terms of the horrors imposed on its victims. Greater atrocities than the Holocaust are imaginable. And we ought to seriously contemplate whether such atrocities might already exist, and realize that there is a risk that atrocities that are much greater still may emerge in the future.

Conclusion

Almost everywhere one finds people discussing contentious issues, nuance and self-scrutiny seem to be in short supply. And yet the most essential point of this essay is not about looking outward and pointing fingers at others. Rather, the point is that if we wish to form more accurate and nuanced perspectives, we need to look in the mirror and ask ourselves some uncomfortable questions.

“How might I be obstructing my own quest for truth?”

“How might my own impulse to signal group loyalty bias my views?”

“What beliefs of mine are mostly serving social rather than epistemic functions?”

We need to remind ourselves of the value of seeking out the grains of truth that may exist in different perspectives so that we can gain a more nuanced understanding that better reflects the true complexity of the world. We need to remind ourselves that our brains evolved to express overconfident and unnuanced views for social reasons — especially in ways that favor our in-group and oppose our out-group. And we need to do a great deal of work to control for this.

None of us will ever be perfect in these regards, of course. Yet we can at least all strive to do better.