It is plausible to assume that technology will keep on advancing along various dimensions until it hits fundamental physical limits. We may refer to futures that involve such maxed-out technological development as “optimized futures”.

My aim in this post is to explore what we might be able to infer about optimized futures. Most of all, my aim is to advance this as an important question that is worth exploring further.

Contents

- Optimized futures: End-state technologies in key domains

- Why optimized futures are plausible

- Why optimized futures are worth exploring

- What can we say about optimized futures?

- Humanity may be close to (at least some) end-state technologies

- Optimized civilizations may be highly interested in near-optimized civilizations

- Strong technological convergence across civilizations?

- If technology stabilizes at an optimum, what might change?

- Information that says something about other optimized civilizations as an extremely coveted resource?

- Practical implications?

- Prioritizing values and institutions rather than pushing for technological progress?

- More research

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgments

Optimized futures: End-state technologies in key domains

The defining feature of optimized futures is that they entail end-state technologies that cannot be further improved in various key domains. Some examples of these domains include computing power, data storage, speed of travel, maneuverability, materials technology, precision manufacturing, and so on.

Of course, there may be significant tradeoffs between optimization across these respective domains. Likewise, there could be forms of “ultimate optimization” that are only feasible at an impractical cost — say, at extreme energy levels. Yet these complications are not crucial in this context. What I mean by “optimized futures” are futures that involve practically optimal technologies within key domains (such as those listed above).

Why optimized futures are plausible

There are both theoretical and empirical reasons to think that optimized futures are plausible (by which I here mean that they are at least somewhat probable — perhaps more than 10 percent likely).

Theoretically, if the future contains advanced goal-driven agents, we should generally expect those agents to want to achieve their goals in the most efficient ways possible. This in turn predicts continual progress toward ever more efficient technologies, at least as long as such progress is cost-effective.

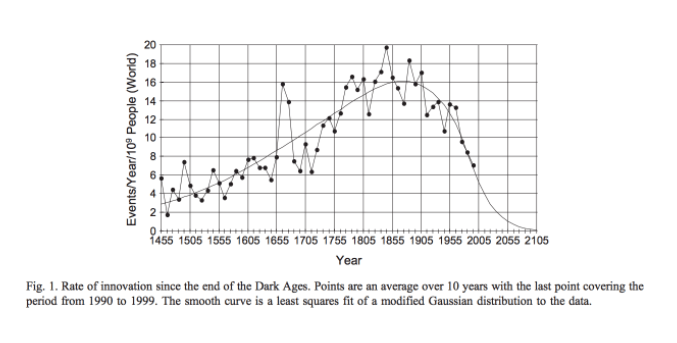

Empirically, we have an extensive record of goal-oriented agents trying to improve their technology so as to better achieve their aims. Humanity has gone from having virtually no technology to creating a modern society surrounded by advanced technologies of various kinds. And even in our modern age of advanced technology, we still observe persistent incentives and trends toward further improvements in many domains of technology — toward better computers, robots, energy technology, and so on.

It is worth noting that the technological progress we have observed throughout human history has generally not been the product of some overarching collective plan that was deliberately aimed at technological progress. Instead, technological progress has in some sense been more robust than that, since even in the absence of any overarching plan, progress has happened as the result of ordinary demands and desires — for faster computers, faster and safer transportation, cheaper energy, etc.

This robustness is a further reason to think that optimized futures are plausible: even without any overarching plan aimed toward such a future, and even without any individual human necessarily wanting continued technological development leading to an optimized future, we might still be pulled in that direction all the same. And, of course, this point about plausibility applies to more than just humans: it applies to any set of agents who will be — or have been — structuring themselves in a sufficiently similar way so as to allow their everyday demands to push them toward continued technological development.

An objection against the plausibility of optimized futures is that there might be a lot of hidden potential for progress far beyond what our current understanding of physics seems to allow. However, such hidden potential would presumably be discovered eventually, and it seems probable that such hidden potential would likewise be exhausted at some point, even if it may happen later and at more extreme limits than we currently envision. That is, the broad claim that there will ultimately be some fundamental limits to technological development is not predicated on the more narrow claim that our current understanding of those limits is necessarily correct; the broader claim is robust to quite substantial extensions of currently envisioned limits. Indeed, the claim that there will be no fundamental limits to future technological development overall seems a stronger and less empirically grounded claim than does the claim that there will be such limits (cf. Lloyd, 2000; Krauss & Starkman, 2004).

Why optimized futures are worth exploring

The plausibility of optimized futures is one reason to explore them further, and arguably a sufficient reason in itself. Another reason is the scope of such futures: the futures that contain the largest numbers of sentient beings will most likely be optimized futures, suggesting that we have good reason to pay disproportionate attention to such futures, beyond what their degree of plausibility might suggest.

Optimized futures are also worth exploring given that they seem to be a likely point of convergence for many different kinds of technological civilizations. For example, an optimized future seems a plausible outcome of both human-controlled and AI-controlled Earth-originating civilizations, and it likewise seems a plausible outcome of advanced alien civilizations. Thus, a better understanding of optimized futures can potentially apply robustly to many different kinds of future scenarios.

An additional reason it is worth exploring optimized futures is that they overall seem quite neglected, especially given how plausible and consequential such futures appear to be. While some efforts have been made to clarify the physical limits of technology (see e.g. Sandberg, 1999; Lloyd, 2000; Krauss & Starkman, 2004), almost no work has been done on the likely trajectories and motives of civilizations with optimized technology, at least to my knowledge.

Lastly, the assumption of optimized technology is a rather strong constraint that might enable us to say quite a lot about futures that conform to that assumption, suggesting that this could be a fruitful perspective to adopt in our attempts to think about and predict the future.

What can we say about optimized futures?

The question of what we can say about optimized futures is a big one that deserves elaborate analysis. In this section, I will merely raise some preliminary points and speculative reflections.

Humanity may be close to (at least some) end-state technologies

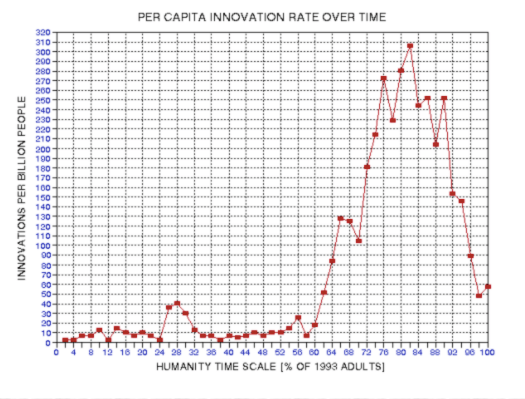

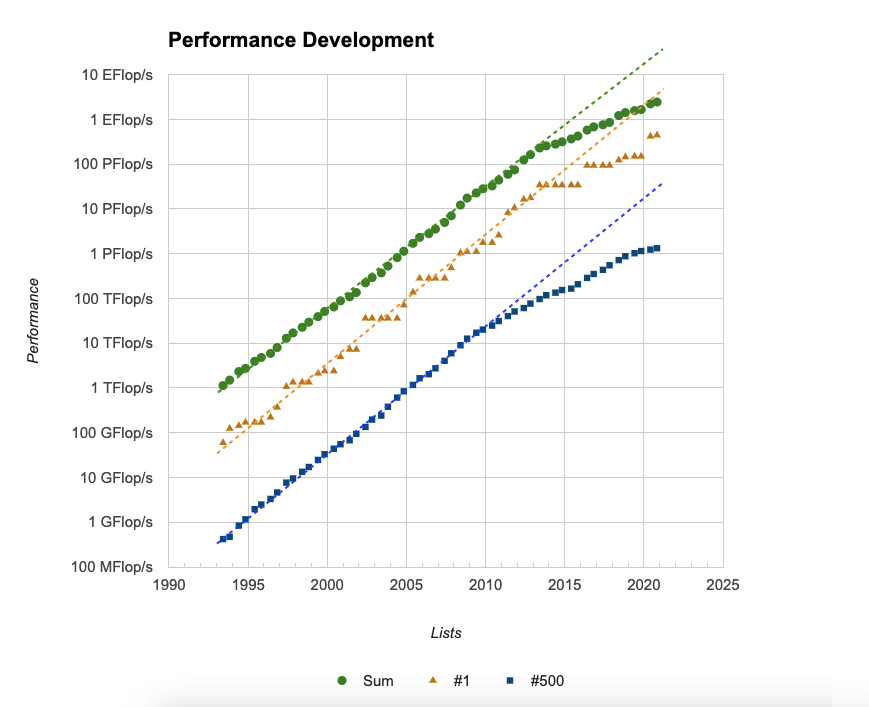

One point that is worth highlighting is that a continuation of current rates of progress seems to imply that humanity could develop end-state technologies in information processing power within a few hundred years, perhaps 250 years at most (if current growth rates persist and assuming that our current understanding of the relevant physics is largely correct).

So at least in this important respect, and under the assumption of continued steady growth, humanity is surprisingly close to reaching an optimized future (cf. Lloyd, 2000).

Optimized civilizations may be highly interested in near-optimized civilizations

Such potential closeness to an optimized future could have significant implications in various ways. For example, if, hypothetically, there exists an older civilization that has already reached a state of optimized technology, any younger civilization that begins to approach optimized technologies within the same cosmic region would likely be of great interest to that older civilization.

One reason it might be of interest is that the optimized technologies of the younger civilization could potentially become competitive with the optimized technologies of the older civilization, and hence the older civilization may see a looming threat in the younger civilization’s advance toward such technologies. After all, since optimized technologies would represent a kind of upper bound of technological development, it is plausible that different instances of such technologies could be competitive with each other regardless of their origins.

Another reason the younger civilization might be of interest is that its trajectory could provide valuable information regarding the likely trajectories and goals of distant optimized civilizations that the older civilization may encounter in the future. (More on this point here.)

Taken together, these considerations suggest that if a given civilization is approaching optimized technology, and if there is an older civilization with optimized technology in its vicinity, this older civilization should take an increasing interest in this younger civilization so as to learn about it before the older civilization might have to permanently halt the development of the younger one.

Strong technological convergence across civilizations?

Another implication of optimized futures is that the technology of advanced civilizations across the universe might be remarkably convergent. Indeed, there are already many examples of convergent evolution in biology on Earth (e.g. eyes and large brains evolving several times independently). Likewise, many cases of convergence are found in cultural evolution in both early history (e.g. the independent emergence of farming, cities, and writing across the globe) as well as in recent history (e.g. independent discoveries in science and mathematics).

Yet the degree of convergence could well be even more pronounced in the case of the end-state technologies of advanced civilizations. After all, this is a case where highly advanced agents are bumping up against the same fundamental constraints, and the optimal engineering solutions in the face of these constraints will likely converge toward the same relatively narrow space of optimal designs — or at least toward the same narrow frontier of optimal designs given potential tradeoffs between different abilities.

In other words, the technologies of advanced civilizations might be far more similar and more firmly dictated by fundamental physical limits than we intuitively expect, especially given that we in our current world are used to seeing continually changing and improving technologies.

If technology stabilizes at an optimum, what might change?

The plausible convergence and stabilization of technological hardware also raises the interesting question of what, if anything, might change and vary in optimized futures.

This question can be understood in at least two distinct ways: what might change or vary across different optimized civilizations, and what might change over time within such civilizations? And note that prevalent change of the one kind need not imply prevalent change of the other kind. For example, it is conceivable that there might be great variation across civilizations, yet virtually no change in goals and values over time within civilizations (cf. “lock-in scenarios”).

Conversely, it is conceivable that goals and values change greatly over time within all optimized civilizations, yet such change could in principle still be convergent across civilizations, such that optimized civilizations tend to undergo roughly the same pattern of changes over time (though such convergence admittedly seems unlikely conditional on there being great changes over time in all optimized civilizations).

If we assume that technological hardware becomes roughly fixed, what might still change and vary — both over time and across different civilizations — includes the following (I am not claiming that this is an exhaustive list):

- Space expansion: Civilizations might expand into space so as to acquire more resources; and civilizations may differ greatly in terms of how much space they manage to acquire.

- More or different information: Knowledge may improve or differ over time and space; even if fundamental physics gets solved fairly quickly, there could still be knowledge to gain about, for example, how other civilizations tend to develop.

- There would presumably also be optimization for information that is useful and actionable. After all, even a technologically optimized probe would still have limited memory, and hence there would be a need to fill this memory with the most relevant information given its tasks and storage capacity.

- Different algorithms: The way in which information is structured, distributed, and processed might evolve and vary over time and across civilizations (though it is also conceivable that algorithms will ultimately converge toward a relatively narrow space of optima).

- Different goals and values: As mentioned above, goals and values might change and vary, such as due to internal or external competition, or (perhaps less likely) through processes of reflection.

In other words, even if everyone has — or is — practically the same “iPhone End-State”, what is running on these iPhone End-States, and how many of them there are, may still vary greatly, both across civilizations and over time. And these distinct dimensions of variation could well become the main focus of optimized civilizations, plausibly becoming the main dimensions on which civilizations seek to develop and compete.

Note also that there may be conflicts between improvements along these respective dimensions. For example, perhaps the most aggressive forms of space expansion could undermine the goal of gaining useful information about how other civilizations tend to develop, and hence advanced civilizations might avoid or delay aggressive expansion if the information in question would be sufficiently valuable (cf. the “info gain motive”). Or perhaps aggressive expansion would pose serious risks at the level of a civilization’s internal coordination and control, thereby risking a drift in goals and values.

In general, it seems worth trying to understand what might be the most coveted resources and the most prioritized domains of development for civilizations with optimized technology.

As hinted above, one of the key objectives of a civilization with optimized technology might be to learn, directly or indirectly, about other civilizations that it could encounter in the future. After all, if a civilization manages to both gain control of optimized technology and avoid destructive internal conflicts, the greatest threat to its apex status over time will likely be other civilizations with optimized technology. More generally, the main determinant of an optimized civilization’s success in achieving its goals — whether it can maintain an unrivaled apex status or not — could well be its ability to predict and interact gainfully with other optimized civilizations.

Thus, the most precious resource for any civilization with optimized technology might be information that can prepare this civilization for better exchanges with other optimized agents, whether those exchanges end up being cooperative, competitive, or outright aggressive. In particular, since the technology of optimized civilizations is likely to be highly convergent, the most interesting features to understand about other civilizations might be what kinds of institutions, values, decision procedures, and so on they end up adopting — the kinds of features that seem more contingent.

But again, I should stress that I mention these possibilities as speculative conjectures that seem worth exploring, not as confident predictions.

Practical implications?

In this section, I will briefly speculate on the implications of the prospect of optimized futures. Specifically, what might this prospect imply in terms of how we can best influence the future?

Prioritizing values and institutions rather than pushing for technological progress?

One implication is that there may be limited long-term payoffs in pushing for better technology per se, and that it might make more sense to prioritize the improvement of other factors, such as values and institutions. That is, if the future is in any case likely to be headed toward some technological optimum, and if the values and institutions (etc.) that will run this optimal technology are more contingent and “up for grabs”, then it arguably makes sense to prioritize those more contingent aspects.

To be clear, this is not to say that values and institutions will not also be subject to significant optimization pressures that push them in certain directions, but these pressures will plausibly still be weaker by comparison. After all, a wide range of values will imply a convergent incentive to create optimized technology, yet optimized technology seems compatible with a wide range of values and institutions. And it is not clear that there is a similarly strong pull toward some “optimized” set of values or institutions given optimized technology.

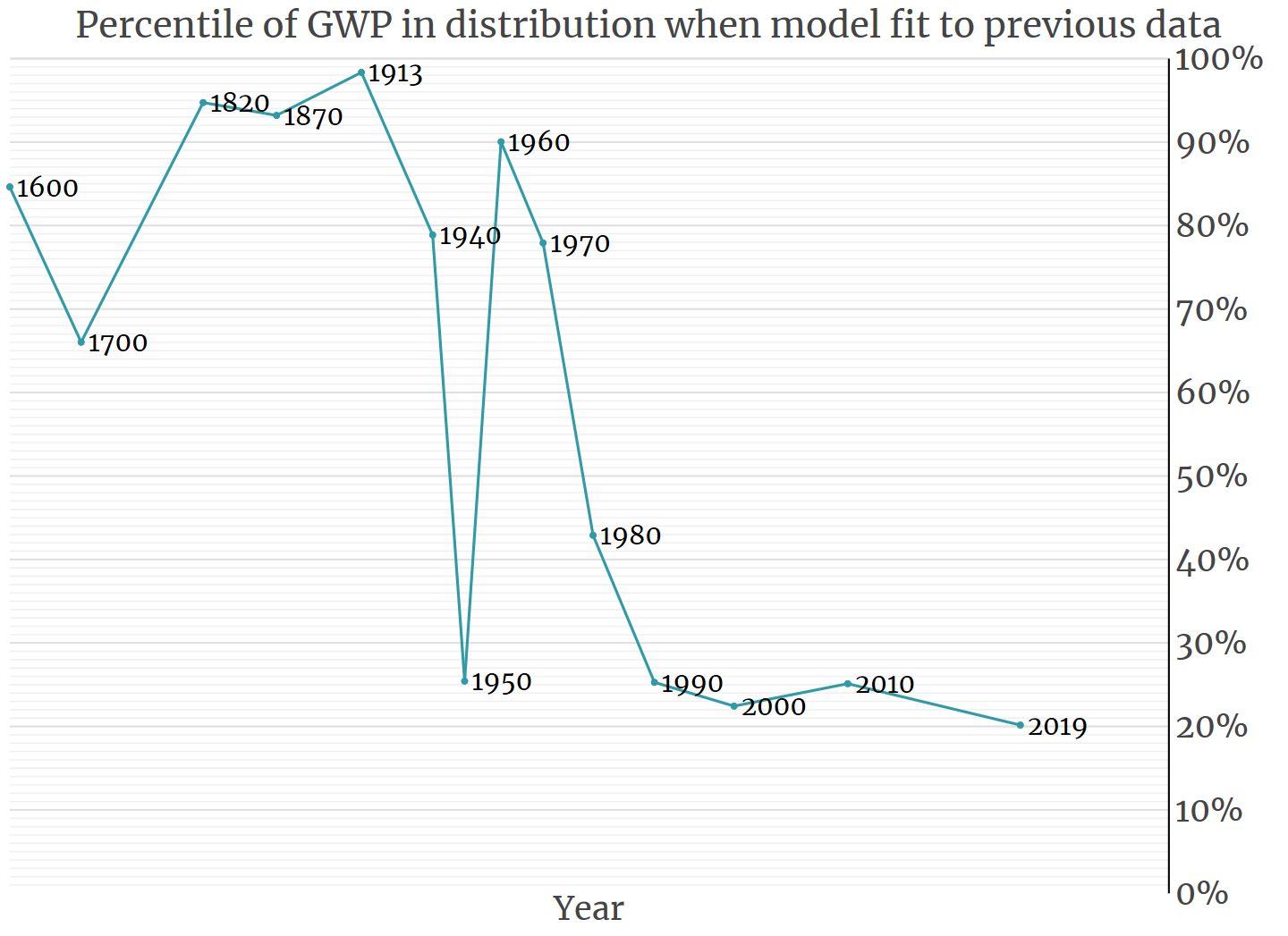

This perspective is arguably also supported by recent history. For example, we have seen technology improve greatly, with computing power heading in a clear upward direction over the past decades. Yet if we look at our values and institutions, it is much less clear whether they have moved in any particular direction over time, let alone an upward direction. Our values and institutions seem to have faced much less of a directional pressure compared to our technology.

More research

Perhaps one of the best things we can do to make better decisions with respect to optimized futures is to do research on such futures. The following are some broad questions that might be worth exploring:

- What are the likely features and trajectories of optimized futures?

- Are optimized futures likely to involve conflicts between different optimized civilizations?

- Other things being equal, is a smaller or a larger number of optimized civilizations generally better for reducing risks of large-scale conflicts?

- More broadly, is a smaller or larger number of optimized civilizations better for reducing future suffering?

- What might the likely features and trajectories of optimized futures imply in terms of how we can best influence the future?

- Are there some values or cooperation mechanisms that would be particularly beneficial to instill in optimized technology?

- If so, what might they be, and how can we best work to ensure their (eventual) implementation?

Conclusion

The future might in some ways be more predictable than we imagine. I am not claiming to have drawn any clear or significant conclusions about how optimized futures are likely to unfold; I have mostly aired various conjectures. But I do think the question is valuable, and that it may provide a helpful lens for exploring how we can best impact the future.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Tobias Baumann for helpful comments.