An earlier post of mine reviewed the most credible evidence I have managed to find regarding seemingly anomalous UFOs. My aim in this post is to mostly set aside the purported UFO evidence and to instead explore whether we can justify placing an extremely low probability on the existence of near aliens, irrespective of the alleged UFO evidence. (By “near aliens”, I mean advanced aliens on or around Earth.)

Specifically, after getting some initial clarifications out of the way, I proceed to do the following:

- I explore three potential justifications for a high level of confidence (>99.99 percent) regarding the absence of near aliens: (I) an extremely low prior, (II) technological impossibility, and (III) expectations about what we should observe conditional on advanced aliens being here.

- I review various considerations that suggest that these potential justifications, while they each have some merit, are often overstated.

- For example, in terms of what we should expect to observe conditional on advanced aliens having reached Earth, I argue that it might not look so different from what we in fact observe.

- In particular, I argue that near aliens who are entirely silent or only occasionally visible are more plausible than commonly acknowledged. The motive of gathering information about the evolution of life on Earth makes strategic sense relative to a wide range of goals, and this info gain motive is not only compatible with a lack of clear visibility, but arguably predicts it.

- For example, in terms of what we should expect to observe conditional on advanced aliens having reached Earth, I argue that it might not look so different from what we in fact observe.

- I try to give some specific probability estimates — Bayesian priors and likelihoods on the existence of near aliens — that seem reasonable to me in light of the foregoing considerations.

- Based on these probability estimates, I present simple Bayesian updates of the probability of advanced aliens around Earth under different assumptions about our evidence.

- I argue that, regardless of what we make of the purported UFO evidence, the probability of near aliens seems high enough to be relevant to many of our decisions, especially those relating to large-scale impact and risks.

- Lastly, I consider the implications that a non-negligible probability of near aliens might have for our future decisions, including the possibility that our main influence on the future might be through our influence on near aliens.

Contents

- My own background with the topic

- Preliminary clarifications

- Real extraordinary UFOs need not imply aliens

- Hypothetical near aliens and expected value: Worth taking seriously even if unlikely

- What can justify confidence about the absence of near aliens?

- I. An extremely low prior in near aliens

- II. Technological impossibility

- III. Not what we should observe conditional on aliens being here

- Puzzling intuitions

- Bayesian updates

- Decision-related implications of hypothetical near aliens

- More research needed

- Acknowledgments

My own background with the topic

Around ten years ago, I was planning to write a short ebook titled Why We Will Never Encounter Intelligent Extraterrestrial Life. The core argument of the book would be based on (1) the vast distances of interstellar space, and (2) the Rare Earth hypothesis and the many “only-happened-once” steps that seem to have been involved in the emergence of technological civilization on Earth (akin to the arguments found here).

So to say that I was skeptical of extraterrestrial life in our vicinity, and to say that I was confident in my skepticism, would be an understatement. I think this background is worth sharing because it gives some sense as to where I am coming from in my approach to this topic. That is, I used to believe, and still do believe, that there are good reasons to be skeptical of the possibility of alien intelligence close to us. But what I have found worth reconsidering and exploring more deeply is the exact nature and strength of those reasons, and whether they can indeed justify the kind of extreme confidence that I used to hold. At this point, I no longer believe that they do.

Preliminary clarifications

This essay contains a lot of speculation and loose probability estimates. It would be tiresome if I constantly repeated caveats like “this is extremely speculative” and “this is just a very loose estimate that I am highly uncertain about”. So rather than making this essay unreadable with constant such remarks, I instead say it once from the outset: many of the claims I make here are rather speculative and they mostly do not imply a high level of confidence. My aim in this essay is to try to reason through a subject that puzzles me and about which I am quite agnostic. I hope that readers will keep this key qualification in mind.

Likewise, I hope readers will not focus too much on the specific probability estimates that I present. These probabilities are not the most central part of this essay. Rather, the central part consists of the object-level considerations that I explore, and my core claims in this essay rest on those considerations themselves, not on any specific probability estimate.

Real extraordinary UFOs need not imply aliens

Another basic clarification is that real UFOs with remarkable abilities would not necessarily have to be aliens. The extraterrestrial hypothesis is just one hypothesis among others, and even if it may be the most plausible one (conditional on extraordinary UFOs being real), we still need to consider the many other hypotheses that also deserve non-negligible weight. These include the hypothesis that some secret human organization has developed craft with remarkable abilities, as well as any other hypothesis that implies an Earth-based origin.

A related clarification is that aliens need not imply animal-like or biological-like aliens, since they could be entirely artificial or otherwise self-designed beyond their original form, which is arguably the most plausible hypothesis (again conditional on extremely advanced aliens being real). After all, any alien civilization capable of visiting Earth would likely be millions of years ahead of us, and it seems unlikely that a technologically advanced species would retain its initial form for so long.

Hypothetical near aliens and expected value: Worth taking seriously even if unlikely

It might be natural to assume that a fairly high probability in near aliens is required for the issue to be worth taking seriously. Yet that is by no means the case. From an expected value perspective, the issue would be worth taking seriously even if there were only, say, a 1 in 10,000 probability of advanced aliens near Earth, especially if we are concerned with analyzing risks that involve large-scale outcomes. Given how consequential it would be if aliens were already here, we seem to have good reason to explore the implications that would follow from such an alien presence. Indeed, this seems true even if we had no reports of UFOs whatsoever, as I will try to argue below. (To clarify, by “worth taking seriously” I do not mean to imply that considerations about near aliens should necessarily weigh strongly in our decisions given a 1 in 10,000 probability, but rather that the issue is worth exploring further and should not be dismissed as irrelevant.)

It is hardly a mystery why we may assume that a high probability of aliens is required for the issue to be worth taking seriously, since that is generally how our intuitive reasoning seems to work. That is, research shows that we are prone to belief digitization, which is the tendency to only consider the single most likely hypothesis in prediction and decision contexts, and to fallaciously disregard all other hypotheses as though they had no relevance whatsoever. Yet it would be a mistake to rely on this rough heuristic of “only consider the single most likely hypothesis” in more serious analyses. For example, any risk analysis that relies on this heuristic would be practically useless.

What can justify confidence about the absence of near aliens?

It is worth asking why many of us are — or have been — so confident about the absence of near aliens (i.e. advanced aliens on or around Earth), seemingly giving it much less than a 1 in 10,000 probability. I am not here interested in sociological explanations of this confidence (e.g. stigma and conformity), but rather in reasons that can provide legitimate justification for confidence in the absence of near aliens.

It seems to me that we can roughly divide the potential justifications into three classes (this resembles the breakdown found in Hanson, 2021):

- I. An extremely low prior in near aliens

- II. Technological impossibility

- III. What we currently see on Earth is not what we should observe conditional on aliens being here

I will explore each of these in turn.

I. An extremely low prior in near aliens

One path to a very low probability in near aliens is to have an extremely low prior to begin with. (What I mean by the “prior” in this context is the probability we would assign to the existence of near aliens given our prior knowledge from fields like cosmology and evolutionary history, before we consider any events that we observe — or fail to observe — on and around Earth today.)

The two main reasons in favor of an extremely low prior in near aliens is the lack of clear signs of advanced aliens in the universe at large (call this the “big empty universe” argument), as well as the apparent rarity of the critical steps that led to intelligent life on Earth (call this the evolutionary argument).

I would agree that both these reasons count in favor of a low prior in near aliens. But the question is how low, especially when we factor in other aspects of our prior knowledge that may point in the opposite direction.

Counterpoints to the “big empty universe” argument

The “big empty universe” argument roughly says that if advanced aliens are common enough to have reached us, then we should expect to see clearly visible signs of advanced aliens in the universe at large (because there would in that case be so many alien civilizations out there, and it seems unlikely that all of them would converge toward policies of low visibility). Therefore, since we do not observe any clear signs of aliens elsewhere, we should conclude that advanced aliens are not near.

What follows are some counterpoints to this argument.

The possibility of panspermia siblings

The absence of clearly visible aliens in the universe at large is not necessarily that strong of a reason to discount near aliens when we consider the possibility of correlated panspermia siblings. This is somewhat analogous to how the apparent rarity of life in general is not a strong reason to be surprised by the existence of non-human animal cousins here on Earth, conditional on our existence. A mostly lifeless universe need not speak strongly against the existence of living relatives in our vicinity.

Of course, the idea that Earth-based life might have panspermia siblings is highly speculative, yet the theoretical possibility still somewhat reduces the force of the “big empty universe” argument.

A priori arguments from theoretical models

A consideration that may weakly raise our credence in the panspermia hypothesis, as well as in the more general hypothesis that key steps in life evolution may have occurred early in our galaxy, is that a number of theoretical frameworks appear to support an earlier origin.

For example, the hard-steps model underlying Hanson et al.’s work on grabby aliens implies that the emergence of advanced civilizations should occur at an increasing frequency over time, and hence hypotheses that imply an earlier origin of the earliest life would a priori be more likely under this model. The related model explored in Snyder-Beattie et al. (2021, sec. 6.3) similarly favors an earlier origin of life, other things being equal (the authors only mention the possibility of an earlier origin on Mars, but their point generalizes to even earlier hypothetical origins).

An unusual galaxy

The “panspermia siblings” hypothesis is just one potential explanation as to why intelligent life might have evolved elsewhere in our galaxy despite not being clearly visible in the universe at large. Another class of explanations is that our galaxy happens to be uniquely suited for the emergence of life, and hence alien life could be close and have somewhat correlated origins with us even if the “panspermia siblings” hypothesis is false.

There is some evidence that our galaxy is indeed a rare outlier in various respects. For instance, our galaxy appears to exist within an unusually empty region of space, adjacent to an unusually large void, while being unusually large for a galaxy positioned at the edge of a “cosmological wall”. It is not yet clear whether these features make our galaxy especially conducive to life, yet it is conceivable that they do.

Relatedly, one could argue that the fact that we have emerged in this galaxy is itself a weak reason to think that our galaxy may be uniquely conducive to the emergence of life. That is, just like there is a Goldilocks zone around stars and within galaxies, there might likewise be an intergalactic Goldilocks zone defined by a unique set of galactic properties. If there is, we should expect to find ourselves — and hypothetical aliens — within that zone. (Note also that the panspermia hypothesis and the Goldilocks hypothesis could be complementary, i.e. intergalactic Goldilocks conditions could help explain why early panspermia happened here, if it did.)

Pseudo-panspermia

A specific way in which our galaxy could have been uniquely conducive to life even without full-blown panspermia is via pseudo-panspermia. In contrast to panspermia, pseudo-panspermia merely entails that many of the smaller organic compounds required for life originated in space. And unlike panspermia, pseudo-panspermia is fairly well-supported; indeed, a number of organic molecules have already been shown to exist in comets and cosmic dust.

Pseudo-panspermia could imply correlated and unusually prevalent life in our galaxy, provided that the “pseudo-panspermic conditions” of our galaxy were uniquely favorable to life. And again, the fact that we are here could be taken as weak support for that conjecture.

In other words, it is conceivable that a substantial part of the great filter (the “filter” that prevents visible large-scale colonization of the cosmos) lies in collecting the “right” mix of organic molecules in the first place, possibly even a unique composition of isotopes. Some perhaps relevant evidence in this regard is that a recent study found that “the chemical nature of the Milky Way is rare among galaxies of its rough shape and structure”. Relevant, too, both to the panspermia and pseudo-panspermia hypotheses, is that “the Milky Way is remarkably efficient at mixing its material, circulating molecules and atoms from the galactic center out into the galaxy’s spiral arms and back”.

Uncertainty about the prevalence of clearly visible aliens given prevalent alien life

That life may have arisen uniquely early and become uniquely prevalent in our particular galaxy is one reason the “big empty universe” argument might not speak strongly against near aliens. Another reason has to do with uncertainty about the prevalence of clearly visible aliens conditional on a high prevalence of alien life.

That is, the “big empty universe” argument against the existence of advanced aliens in our galaxy assumes that we would see clear signs of life elsewhere (i.e. beyond our galaxy) if advanced alien life were prevalent in the universe at large. Yet just how sure can we be about this claim? Even if we grant that we would most likely see unmistakable signs of alien life if such life were prevalent, it seems that we still have some reasons to doubt that we would.

For example, we can hardly rule out that the ratio of “advanced aliens who are clearly visible” to “advanced aliens who are not clearly visible” (from vast distances) could be extremely low. After all, there might be strong strategic reasons not to become a clearly visible civilization, or to greatly postpone clearly visible activity. One of these reasons might be the info gain motive mentioned below. (For other potential reasons for expansionist aliens to be quiet, see e.g. this section.)

In light of these considerations, it seems reasonable to me to assign at least a 5 percent probability to observing roughly what we observe even assuming that advanced aliens are fairly prevalent throughout the universe. (To be specific, “fairly prevalent” could here mean something like 1 advanced alien civilization per 100 large galaxies.)

Note that our uncertainty about alien visibility from vast distances is an independent reason to lower the force of the “big empty universe” argument, distinct from the reasons relating to the potentially correlated origin of near aliens.

A moderate prevalence of life + a moderate visibility ratio need not imply current visibility

Let us define the ‘visibility ratio’ as the ratio of advanced aliens who are “clearly visible” to those who are “not clearly visible” when observed from a vast distance within their future light cone. The “big empty universe” argument can seem to imply that we must assume an extremely low visibility ratio in order for intergalactic advanced aliens to be here and for us to not see clearly visible aliens in the universe at large. However, by taking a closer look and inserting some specific numbers, we see that this is not necessarily the case.

For example, say that we assume an average concentration of one advanced alien civilization per sphere with a radius of 300 million light years throughout the universe. Such a concentration could imply that advanced aliens from another galaxy would have been able to reach us by now. For instance, they could be the average advanced civilization from within our 300 Mly sphere, or they could even be from an adjacent sphere, provided that they originated around 600 million years ago.

Yet this concentration would also imply that the lack of clearly visible aliens in the universe at large is not strong evidence against the existence of near aliens given a moderate visibility ratio. For as we look beyond a radius of a few hundred million light years, the light that reaches us becomes increasingly out of date and thus requires increasingly early alien origins for us to observe any signs of them.

Hence, uncorrelated advanced aliens could be near, moderately prevalent throughout the universe, not yet visible, and have a moderate visibility ratio — say, 1 in 3 or even higher. The ratio can be higher or lower depending on the exact concentration and how recently we assume advanced aliens to have appeared. For example, if one thinks that a substantial fraction of advanced aliens likely appeared much earlier than a few hundred million years ago, then near aliens could likewise be much older and from much further away (e.g. from 2 billion light years away), and thus earlier origins and a lower concentration of distinct expansionist aliens could still imply near-alien presence, no current large-scale visibility, and a moderate-to-high visibility ratio. (Indeed, if we consider observer selection effects, the visibility ratio could even be extremely high, as we in that case arguably should expect to find ourselves within a large pocket of “not clearly visible” colonization.)

This point about how uncorrelated near aliens need not imply an extremely low visibility ratio is yet another independent point against the “big empty universe” argument, on top of both the possibility of correlated origins and the possibility of a low visibility ratio. Thus, when evaluating the probability of near aliens in an apparently empty universe, we should separately assign some weight to the hypotheses of “correlated origins”, “uncorrelated origins + a low visibility ratio”, and “uncorrelated origins + a moderate visibility ratio and concentration”.

Counterpoints to the evolutionary argument

What about the observation that many of the critical steps in the history of life appear to have happened only once? I see at least two reasons why this is not a strong point against the existence of near aliens.

A potentially large number of habitable planets

The number of planets in the Milky Way Galaxy is estimated to be around 100 to 300 billion. Research suggests that 300 million of these could be habitable, perhaps many more; and a non-trivial fraction of these planets might in some sense be more habitable than Earth. With such a large number of potentially habitable planets, it seems difficult to confidently exclude that intelligent life might have evolved elsewhere in our galaxy, even if we grant that the evolution of intelligent life requires some exceedingly rare events.

Moreover, as noted earlier, our galaxy is by no means the only conceivable place from which hypothetical near aliens could have originated. If we go beyond our galaxy and look at, say, the ~2,500 large galaxies that exist within a radius of 100 million light years, a crude extension of the Milky Way estimates above would suggest that these galaxies contain around 250 to 750 trillion planets, and around 750 billion habitable planets. Extending this estimate to a radius of 300 million light years, we get 67,500 large galaxies with 7 to 20 quadrillion planets and around 20 trillion habitable planets. These staggering numbers make it much less plausible still to be confident about the absence of near aliens based on our own evolutionary history.

Crowding out evolutionary niches

The fact that many critical events seem to have happened only once on Earth is not necessarily strong evidence as to how often similar events might occur across different habitable environments, such as other planets. After all, it seems plausible that at least some evolutionary developments only happen once because they in effect crowd out a particular niche, thereby preventing similar steps from happening again in the same environment (cf. the competitive exclusion principle). This is not to deny that many of the events involved in the evolution of life on Earth are rare, but the crowding-out consideration does serve to question just how rare we should infer them to be based on our limited knowledge of evolutionary histories (n=1).

All-things-considered probability estimates: Priors on near aliens

Where do all these considerations leave us? In my view, they overall suggest a fairly ignorant prior. Specifically, in light of the (interrelated) panspermia, pseudo-panspermia, and large-scale Goldilocks hypotheses, as well as the possibility of near aliens originating from another galaxy, I might assign something like a 10 percent prior probability to the existence of at least one advanced alien civilization that could have reached us by now if it had decided to. (Note that I am here using the word “civilization” in a rather liberal sense; for example, a distributed web of highly advanced probes would count as a civilization in this context.) Furthermore, I might assign a probability not too far from that — maybe around 1 percent — to the possibility that any such civilization currently has a presence around Earth (again, as a prior).

Why do I have something like a 10 percent prior on there being an alien presence around Earth conditional on the existence of at least one advanced alien civilization that could have reached us? In brief, one of the main reasons is the info gain motive that I explore at greater length below. Moreover, as a sanity check on this conditional probability, we can ask how likely it is that humanity would send and maintain probes around other life-supporting planets assuming that we became technologically capable of doing this; roughly 10 percent seems quite sane to me.

At an intuitive level, I would agree with critics who object that a ~1 percent prior probability in any kind of alien presence around Earth seems extremely high. However, on reflection, I think the basic premises that get me to this estimate look quite reasonable, namely the two conjunctive 10-percent probabilities in “the existence of at least one advanced alien civilization that could have reached us by now if it had decided to” and “an alien presence around Earth conditional on the existence of at least one advanced alien civilization that could have reached us”.

Note also that there are others who seem to defend considerably higher priors regarding near aliens (see e.g. these comments by Jacob Cannell; I agree with some of the points Cannell makes, though I would frame them in more uncertain and probabilistic terms).

I can see how substantially lower priors than mine could be defensible, even a few orders of magnitude lower, depending on how one weighs the relevant arguments. Yet I have a hard time seeing how one could defend an extremely low prior that practically rules out the existence of near aliens. (Robin Hanson has likewise argued against an extremely low prior in near aliens. See also my more recent posts “From AI to distant probes” and “Silent cosmic rulers”, which both present arguments that support a fairly high prior in near aliens.)

II. Technological impossibility

Another potential justification for a very low probability in near aliens has to do with claims about technological impossibility. That is, the technology that would be required seems impossible, and therefore we have strong reasons to doubt that aliens could be present around Earth.

This claim is relevant in at least two ways. First, it is relevant to the possibility of alien visits to Earth: could they even travel from their planet of origin to here in the first place? Second, it is relevant to how we evaluate purported UFO sightings: could hypothetical aliens have technology capable of the advanced feats that various pilots have reported, such as extreme acceleration and flying without visible means of propulsion?

These two questions belong to separate parts of our analysis — the prior and the likelihood, respectively — yet it seems worth treating them together in light of their similarity. Indeed, I would argue that the same basic line of reasoning applies to both cases. That line of reasoning is as follows: for any civilization that is millions, or even just several thousands, of years ahead of us in terms of their scientific and technological development, we should not be particularly confident that they could not eventually achieve capabilities at this level. (It is also worth noting that there is some theoretical speculation as to how reported UFO capabilities could be physically possible, essentially by manipulating gravity.)

Specifically, it seems to me that we can hardly defend placing much less than 50 percent probability on the claim that an advanced civilization that is countless generations ahead of ours would possess capabilities like these. After all, such a civilization would presumably have exceedingly advanced AI, physics, materials science, and so on.

(I should clarify that this ~50 percent probability estimate does not change my prior listed in the previous section, since the implied ~50 percent probability that hypothetical aliens would not be able to travel through the galaxy is already factored into that prior.)

Overall, I suspect that most analysts would not give this technology-related objection as their main reason for doubting that aliens could be present around Earth, at least not on reflection. However, I suspect that many of us might nevertheless feel like it is a strong reason at an intuitive level, in which case we may need to adjust our intuitions. That being said, I think the need to update our intuitions is much greater when it comes to the third and final point, namely what we should expect to see if advanced aliens were in fact present around Earth.

III. Not what we should observe conditional on aliens being here

It is my impression that, at least for many people, by far the strongest reason to be confident that there are no near aliens is that the events we currently see on and around Earth are not what we should observe conditional on advanced aliens being here. But just how strong is this reason, and is it a strong reason at all? On closer examination, it seems to me that it is not.

Why so confident?

The assumption seems to be that if advanced aliens were here, they should be clearly visible and leave no doubt as to their presence. Yet this is a rather strong assumption. After all, there is a fairly broad class of motives for not being clearly visible, and we can hardly claim to be confident that advanced aliens would not have motives within that rather broad class of motives.

As Robin Hanson writes: “If we often have trouble explaining the behaviors of human societies and individuals, I don’t think we should feel very confident in predicting detailed behaviors of a completely alien civilization.” Hanson has speculatively proposed some specific explanations for not clearly visible aliens, such as particular values or strategies for gradually causing humanity to submit, and he suggests that there are many other possible explanations as to why advanced aliens might be quiet (conditional on them being here).

The info gain hypothesis

To my mind, Hanson’s specific explanations are not even among the most plausible ones. As I see it, the most plausible explanation for advanced alien visits to Earth is to gain information about the evolution of life on Earth, including our future evolution. We may call this the “info gain hypothesis” regarding the key motive for advanced alien visitation to Earth, conditional on them being here. (Of course, this motive can co-exist with other motives, such as preventing us from eventually rivaling their technology and colonizing space.)

To be clear, when I say that this seems to me the most plausible motive, this is not to say that I would necessarily place the majority of my probability mass on this motive, but rather that I would place a plurality of my probability mass on it (conditional on them being here). That is, I would assign a higher probability to this motive compared to any other single category of motives.

It is worth noting that many people seem to agree that this is a plausible motive. For example, in a Twitter poll conducted by Hanson (n=1,243), more than 65 percent of people thought that the most likely strongest motive for alien UFO visits to Earth would be to “study us as [an] independent example of life evolution”. And there is indeed much to be said in favor of the plausibility of this motive.

The plausibility of the info gain motive

Perhaps the main reason that supports the info gain motive is the potentially extreme value of information concerning the evolution of life on Earth. Or expressed in more general terms: it may be extremely valuable to study any life-supporting planet in order to better understand the distribution of evolutionary trajectories across life-supporting planets.

There are a few reasons why this could be exceptionally valuable. First, even if we grant the existence of near aliens, it still seems likely that the evolution of complex life — let alone civilizations — is quite rare in the universe at large. Perhaps there are only a few civilizations within the (hypothetical) near aliens’ reach, in which case there would be a large info gain to studying life on Earth: it would constitute a large relative update in the expected distribution of evolutionary trajectories.

Second, apart from its potential rarity, the information could be valuable because it might inform highly consequential decisions in the far future. For example, say that we assume some version of the grabby aliens picture, and thus assume that multi-galaxy-spanning alien civilizations will meet each other in the future. Under that kind of scenario, perhaps the best way for expansionist civilizations to learn about the likely trajectory of other expansionist aliens (whom they will eventually meet) is to study emerging civilizations within their own reach. This might help them prepare their strategies for those cosmic meetings.

After all, even if we assume that expansionist civilizations would be able to run sophisticated simulations of other expansionist civilizations, those simulations would likely be significantly more accurate if they were based on data from real-world evolutionary trajectories. And the relevant data need not be restricted to data about the kinds of life forms and cultural groups that have actually built civilizations; it may also include the many life forms and cultural groups that did not develop into a powerful civilization, but which potentially could have under slightly different circumstances. Such broad data may not only help predict what other expansionist civilizations might be like, but also how prevalent and how far away they are likely to be.

A third reason to study us might be to better understand how to best deal with us and prevent us from eventually developing to the point where we can pose a threat to them. However, this can hardly be the main reason for studying us. After all, if the overriding goal were to prevent life on Earth from developing to the point of threatening them, they would presumably have neutralized that threat long ago.

Info gain as a plausible explanation for a lack of clear visibility

The info gain motive also tentatively predicts that the advanced aliens should not be clearly visible (I might give ~75 percent probability to “no clear visibility” conditional on them being here and having this motive). After all, ideas of non-reactive research, unobtrusive research, and the like are familiar from social science and animal studies, and the justification for such methodologies is fairly straightforward: if one interferes (too strongly) with the phenomenon under investigation, one risks dictating or otherwise distorting its outcome.

However, an info gain motive is also compatible with a certain level of experimentation, which could take the form of some occasionally visible interferences in order to test the reaction. So the info gain motive does not necessarily predict complete silence, even if it mostly predicts a not clearly visible presence.

Info gain as further (weak) support for a modestly high prior in near aliens

As hinted earlier, the plausibility of the info gain motive is also relevant to our prior. For example, if we combine a strong info gain motive with the above-mentioned hard-steps model, this would imply a scenario in which the very first advanced civilization in our region of the cosmos would (mostly) quietly study other alien life forms and civilizations that emerge later at an increasing rate over time. And within this scenario, we should a priori expect ourselves to be among the more numerous later observees rather than the one very first (eventual) cosmic observer.

All-things-considered probability estimates: Likelihoods on near aliens

In light of the points raised above, what rough probability would I assign to advanced aliens being quiet, or not clearly visible, conditional on them being present around Earth (and conditional on our being here on Earth and not seeing clear signs of aliens in the universe at large)? As with all the numbers I give in this essay, the following are just rough numbers that I am not adamant about defending; I can readily see how different numbers can be defended.

I might place ~10 percent probability on advanced aliens being completely quiet conditional on them being present, meaning that they would leave no observable trace, not even occasionally visible UFOs. In addition, I might place ~30 percent probability on them being occasionally visible, yet without being clearly visible. That leaves roughly 60 percent probability mass on clear visibility conditional on them being here; this could include outcomes where they continuously engage in unmistakable acts of aggression, diplomacy, or experimentation. (Of course, “visibility” is gradual and could be subdivided into many levels, but I have here chosen three rough categories for simplicity.)

I think a combined ~40 percent probability in “not clearly visible conditional on them being here” is reasonable in light of the plausibility of the info gain motive, which seems instrumentally rational for a wide range of future goals. (If the info gain motive is so plausible, then why not assign an even higher probability than 40 percent to “not clearly visible” conditional on them being here? Partly because we should also give some probability to seeing “clearly visible” activity given the info gain motive, such as overt and continuous experimentation, and partly because there are alternative motives that would mostly imply “clear visibility”.)

What explains my ~10 percent in “totally quiet” conditional on them being here? The main reasons I would give are the desire not to disturb the phenomenon under investigation and the presumably high level of technological sophistication of a much older alien civilization, which might allow them to leave no trace whatsoever.

What explains my ~30 percent in “occasionally visible”? Despite the point made above, extensive studies still seem likely to involve some occasionally visible traces, either as an unavoidable side effect or as a deliberate consequence of an experimental procedure. And again, as noted by Hanson, there are other motives besides the info gain motive that could imply occasional visibility, such as gradually causing humanity to submit or get assimilated. Note also that the info gain motive and the assimilation motive could be complementary: perhaps an alien civilization would see value in not only studying our evolution but also in assimilating and preserving Earth as a living library of sorts.

Puzzling intuitions

Before putting all these probability estimates together, it seems worth briefly reflecting on the core intuition explored in the previous section. That is, as hinted above, it seems that many people are intuitively confident that advanced aliens should be clearly visible conditional on them being here. But this seems puzzling considering the plausibility of the info gain motive, and not least considering that the plausibility of this motive seems widely accepted (cf. the earlier-mentioned poll). Moreover, it is quite likely that this is what we ourselves would do if we were to discover alien life on another planet, namely to study it with minimal interference. So why would our intuitions largely disregard this motive when considering hypothetical near aliens?

I suspect that part of the reason behind this intuition is that we may fail to intuit just how technologically advanced aliens might be. An interesting contrast in this regard is how an increasing number of people are talking about the potential abilities of future AI systems, and about how these systems might eventually be able to hide and make plans that we cannot readily understand. At the level of our intuitions, many of us seem to view near-term AI systems as far more capable than hypothetical advanced aliens with a presence around Earth. Yet the relationship would most likely be the opposite: the probes of an advanced alien civilization would be far more powerful than any self-improving AI system whose knowledge and technology are millions of years behind.

Indeed, just as some have speculated that future technology might make it possible to have a galaxy-scale population on Earth, one can similarly speculate that advanced technology could allow near aliens to fit more than the existing (effective) computing power of present-day Earth into a one-meter orb (cf. Lloyd, 2000). Thus, if our intuitions are out of touch when it comes to how advanced and inscrutable near-term AI systems might be, they seem completely out of touch as to how advanced and inscrutable hypothetical near aliens might be.

In any case, my point here is simply that it seems worth noticing whether we have strong intuitions about what we should observe conditional on advanced aliens being present, and to reflect on whether strong intuitions are justified.

Bayesian updates

My aim in this section is to present some Bayesian updates based on the estimates provided in the earlier sections. I will seek to provide two distinct posterior probabilities regarding near aliens, one in which our observed evidence is assumed to be “no trace of truly unusual UFOs”, and one in which the observed evidence is assumed to be “occasional sightings of truly unusual UFOs”. As hinted earlier, these are exceptionally broad and rough categories that could be partitioned much further, but they are helpful for keeping the analysis simple.

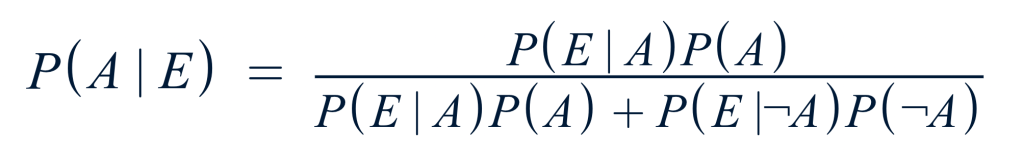

The general formula for the posterior probability is the following, where A is the hypothesis “advanced aliens around Earth”, E is the evidence, P(A) is the prior, and P(E|A) is the likelihood:

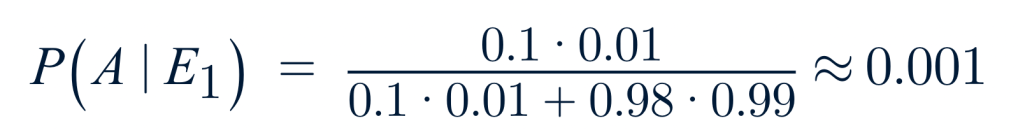

In the case of the first assumption about our observed evidence — “no trace of anything truly unusual” — my loose estimates imply the following:

In other words, a 0.1 percent posterior probability of advanced aliens around Earth given the 1 percent prior and no trace of anything unusual. The evidence (only) reduced the prior by a factor of around 10 due to the estimated 10 percent probability of advanced aliens leaving no trace conditional on them being here. (The only new estimate introduced in the equation above is the 98 percent probability of seeing no truly unusual UFOs conditional on there being no advanced aliens around Earth.)

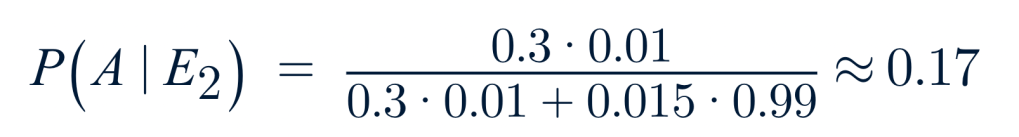

Next, we have the assumption that our evidence is “occasional sightings of truly unusual UFOs”, where my rough estimates imply the following:

The posterior update is perhaps weaker than one might expect. The reason it is not stronger is partly the significant probability mass on something other than “occasional visibility” conditional on advanced aliens around Earth, and partly the non-trivial probability — around 1.5 percent in my rough estimate — of occasionally seeing truly unusual UFOs conditional on there being no near aliens, such as secret human-created or otherwise non-alien craft.

Of course, this is a rather crude and preliminary analysis. One could potentially refine it by looking at more specific predictions and evidence. For example, one could look at the predictions that would follow from the info gain motive in particular, and then explore the evidence related to those predictions. Specifically, one could argue that the info gain motive plausibly implies that hypothetical near aliens should be willing to make occasional interventions in order to prevent human self-destruction, since such preventive efforts would likely increase their info gain (after all, one would presumably learn more about future expansionist aliens from civilizations that survived rather than from those that went extinct or collapsed). And one could then try to hold that prediction up against the numerous reports made by nuclear missile launch officers regarding UFOs interfering with nuclear weapons.

Such further investigations are beyond the scope of this post. What I will say, to share my own two cents, is that it seems to me that our observed evidence is more akin to “occasional sightings of truly unusual UFOs” than to “no trace of truly unusual UFOs”. For instance, it is difficult for me to see how one can take a closer look at the Nimitz incident and conclude that any conventional explanation like birds, balloons, helicopters, or drones is a plausible explanation of the totality of the evidence (e.g. the reports from David Fravor, Alex Dietrich, and Kevin Day).

However, the main point I would stress in light of the preceding analysis does not rest on the specific UFO evidence that we may or may not have, nor does it rest on any given interpretation of this evidence. In my view, perhaps the most important takeaway is that even assuming “no trace of truly unusual UFOs”, it seems that the probability of advanced aliens around Earth, while not high in absolute terms, is still high enough for us to take this possibility into account in our decisions going forward. From a perspective concerned with large-scale influence, a 1 in 1,000 probability of advanced aliens around Earth — and even a substantially lower probability than that — makes it worth exploring what the decision-related implications might be.

Decision-related implications of hypothetical near aliens

As with everything else in this essay, the following will be a highly incomplete discussion. I should also clarify that the decision-related implications that I here speculate on are not meant as anything like decisive or overriding considerations. Rather, I think they would mostly count as weak to modest considerations in our assessments of how to act, all things considered. (Of course, the exact strength of these considerations will depend on our exact probability in near aliens.)

Influencing future alien actions?

Perhaps the main implication of (a non-negligible probability of) near aliens is that we might be able to influence their expectations and future actions. That is, if aliens have reached Earth, they are likely far more powerful than us, and they likely prefer to keep things that way, suggesting that most of our influence on the long-term future might be through our influence on them.

How could we possibly influence their future actions if they are so much more powerful than us? One way is by influencing their expectations about how other aliens in the universe might act. For example, if we act in a hostile way, such as by preparing to fight them, the near aliens might (marginally) update their expectations toward future conflict with other expansionist aliens. Conversely, if we show a willingness to cooperate, they might update their expectations toward greater cooperation.

One may object that near aliens would take our efforts to influence them into account, and hence we should not expect that any such efforts to influence them would make any difference. Yet even if hypothetical near aliens were aware of our intentions to influence them, our actions could still count as (weak) evidence regarding how other real-world agents might act in the future, and thus still exert some influence. For example, our actions might provide some information about the distribution of values and decision strategies among real-world agents more broadly, agents who might face similar conditions of uncertainty as we do.

Assuming that we could influence near-alien expectations, how should we ideally influence them? Should we try to nudge them to prepare for conflict or cooperation? The answer is hardly clear. While it may feel intuitively obvious to say “cooperation”, it is conceivable that “conflict” might be better — for instance, if far expansionist aliens will be much worse than our near aliens, and if conflict preparations best enable our near aliens to win or otherwise create better outcomes. Of course, cooperation versus conflict is not the only relevant aspect to consider; it is just one example of the kinds of questions that might be worth exploring when it comes to such hypothetical alien influence.

Seeking a better understanding

A better understanding of the near aliens would be helpful for our decisions in this regard, and seeking such a better understanding would likely be a top priority conditional on their existence. From a circumstance of high uncertainty about their existence, it is obviously less of a priority, but it is probably still worth devoting some resources toward it, at least by some people.

Quite a bit has been written about the speculative possibility of understanding and cooperating with distant aliens (e.g. in the context of “acausal trade” and “Multiverse-wide cooperation”). Yet relatively little serious analysis seems to have been done on the possibility of understanding and interacting with hypothetical near aliens (which is also speculative, to be sure, though perhaps less so).

How to better understand near aliens

How, specifically, could we seek to gain a better understanding of hypothetical near aliens? One way might be to engage in informed theorizing to see whether we can draw any sensible inferences about them based on their lack of clear visibility (conditional on their presence). Another strategy would be to explore purported UFO reports in order to see whether any informative patterns might emerge. For instance, one could explore whether the many UFO reports connected with nuclear weapons are indicative of any consistent set of motives. A third strategy might be to seek out new data, such as by using advanced sensor technology to track purported UFO hotspots (see e.g. UAPx).

To be clear, none of these investigative efforts require us to assume that near aliens actually exist. And, of course, efforts like these may be unlikely to yield any clear or highly useful results, but they could still be worth pursuing given both the potential stakes and the neglectedness of the issue.

Wagers to focus on human-controlled scenarios versus alien-controlled scenarios

Regarding the potential stakes, one could argue that there is a wager against focusing on scenarios in which we mostly influence the long-term future through our — perhaps at best modest — effects on near aliens. In other words, one could argue that our influence on the future seems rather limited in this class of scenarios, which gives us reason to instead focus on scenarios in which we can determine our long-term future ourselves.

I think this is a sensible point, but I see at least two arguments that may push against it. First, the validity of the argument above seems to depend on who “we” are. Specifically, if “we” are a group of marginal actors who try to steer the future in a slightly better direction, then it is hardly clear whether our influence on human descendants would necessarily be greater than our influence on advanced near aliens (conditional on their existence). Indeed, one may argue that our influence on near aliens could be greater in some ways, as they might be less resistant to updating their views, be better informed about our actions, have broader attention bandwidth, and so on, compared to humanity at large.

Second, the wager to focus on vast human-controlled futures seems weakened by a wager in the opposite direction, namely a wager to focus on vast futures controlled by near aliens. And one could argue that the latter wager is stronger in some important ways. After all, if advanced near aliens exist, they are already an expansive species with cosmic-scale influence, whereas humans seem quite far from reaching that stage, and might well never reach it. Thus, a low probability of a human-controlled cosmic future could imply that the wager on near alien influence is overall stronger, even given uncertainty about their existence. To be clear, I am not saying that I endorse this argument, but it does seem worth considering, especially in a generalized form that pertains to our influence on all future aliens that might potentially learn about and be influenced by us.

Updating toward more of a short-term focus?

Another implication might be to update more toward helping beings in the short term. In particular, if one believes that near aliens would govern the long-term future in a mostly predecided manner regardless of what humans do, then a greater probability in near aliens would shift a greater fraction of our expected impact toward the short term. After all, under those assumptions, our expected impact on the long-term future would be greatly reduced by near aliens, yet our potential to help fellow beings in the short term would be largely unchanged.

Thus, somewhat ironically, (greater degrees of) belief in near aliens could ultimately push us toward more commonsensical priorities in altruistic endeavors.

More research needed

The remarks above have barely scratched the surface. In light of the considerations reviewed in this essay, it seems to me that more serious attention to the possibility of near aliens is warranted, especially in terms of its potential implications for our decisions.

Acknowledgments

For helpful comments, I thank Teo Ajantaival, David Althaus, Tobias Baumann, Mathias Kirk Bonde, Tristan Cook, and Robin Hanson.