The prospect of smarter-than-human artificial intelligence (AI) is often presented and thought of in terms of a simple analogy: AI will stand in relation to us the way we stand in relation to chimps. In other words, AI will be qualitatively more competent and powerful than us, and its actions will be as inscrutable to humans as current human endeavors (e.g. science and politics) are to chimps.

My aim in this essay is to show that this is in many ways a false analogy. The difference in understanding and technological competence found between modern humans and chimps is, in an important sense, a zero-to-one difference that cannot be repeated.

Contents

- How Are Humans Different from Chimps?

- I. Symbolic Language

- II. Cumulative Technological Innovation

- The Range of Human Abilities Is Surprisingly Wide

- Why This Is Relevant

How Are Humans Different from Chimps?

A common answer to this question is that humans are smarter. Specifically, at the level of our individual cognitive abilities, humans, with our roughly three times larger brains, are just far more capable.

This claim no doubt contains a large grain of truth, as humans surely do beat chimps in a wide range of cognitive tasks. Yet it is also false in some respects. For example, chimps have superior working memory compared to humans, and they can apparently also beat humans in certain video games, including games involving navigation in complex mazes.

Researchers who study human uniqueness provide some rather different, more specific answers to the question. If we focus on individual mental differences in particular, researchers have found that, crudely speaking, humans are different from chimps in three principal ways: 1) we can learn language, 2) we have a strong orientation toward social learning, and 3) we are highly cooperative (among our ingroup, compared to chimps).

These differences have in turn resulted in two qualitative differences in the abilities of humans and chimps in today’s world.

I. Symbolic Language

The first qualitative difference is that we humans have acquired an ability to think and communicate in terms of symbolic language that represents complex concepts. We can learn about the deep history of life and about the likely future of the universe, including the fundamental limits to space travel and future computations given our current understanding of physics. Any educated human can learn a good deal about these things whereas no chimp can.

Note how this is truly a zero-to-one difference: no symbolic language versus advanced symbolic language through which knowledge can be represented and continually developed (Deacon, 1997, ch. 1). It is the difference between having no science of physics versus having an extensive such science with which we can predict future events and estimate some hard limits on future possibilities.

In many respects, this zero-to-one difference cannot be repeated. Given that we already have physical models that predict, say, the future motion of planets and the solar system to a high degree of accuracy, the best one can do in this respect is to (slightly) improve the accuracy of these predictions. Such further improvements cannot be compared to going from zero conceptual physics to current physics.

The same point applies to our scientific understanding more generally: we currently have theories that work decently at explaining most of the phenomena around us. And while one can significantly improve the accuracy and sophistication of many of these theories, such further improvements will likely be less significant than the qualitative leap from absolutely no conceptual models to the entire collection of models and theories that we currently have.

For example, going from no understanding of evolution by natural selection to the elaborate understanding of biology we have today can hardly be matched, in terms of qualitative and revolutionary leaps, by further refinements in biology. We have already mapped out the core basics of biology, especially when it comes to the history of life on Earth, and this can only be done once.

The point that the emergence of conceptual understanding is a kind of zero-to-one step has been made by others. Robin Hanson has made essentially the same point in response to the notion that future machines will be “as incomprehensible to us as we are to goldfish”:

This seems to me to ignore our rich multi-dimensional understanding of intelligence elaborated in our sciences of mind (computer science, AI, cognitive science, neuroscience, animal behavior, etc.).

… the ability of one mind to understand the general nature of another mind would seem mainly to depend on whether that first mind can understand abstractly at all, and on the depth and richness of its knowledge about minds in general. Goldfish do not understand us mainly because they seem incapable of any abstract comprehension. …

It seems to me that human cognition is general enough, and our sciences of mind mature enough, that we can understand much about quite a diverse zoo of possible minds, many of them much more capable than ourselves on many dimensions.

Ramez Naam has argued similarly in relation to the idea that there will be some future time or intelligence that current humans are fundamentally unable to understand. He argues that our understanding of the future is growing rather than shrinking as time progresses, and that AI and other future technologies will not be beyond comprehension:

All of those [future technologies] are still governed by the laws of physics. We can describe and model them through the tools of economics, game theory, evolutionary theory, and information theory. It may be that at some point humans or our descendants will have transformed the entire solar system into a living information processing entity — a Matrioshka Brain. We may have even done the same with the other hundred billion stars in our galaxy, or perhaps even spread to other galaxies.

Surely that is a scale beyond our ability to understand? Not particularly. I can use math to describe to you the limits on such an object, how much computing it would be able to do for the lifetime of the star it surrounded. I can describe the limit on the computing done by networks of multiple Matrioshka Brains by coming back to physics, and pointing out that there is a guaranteed latency in communication between stars, determined by the speed of light. I can turn to game theory and evolutionary theory to tell you that there will most likely be competition between different information patterns within such a computing entity, as its resources (however vast) are finite, and I can describe to you some of the dynamics of that competition and the existence of evolution, co-evolution, parasites, symbiotes, and other patterns we know exist.

Chimps can hardly understand human politics and science to a similar extent. Thus, the truth is that there is a strong disanalogy between the understanding that chimps have of humans versus the understanding that we humans — thanks to our conceptual tools — can have of any possible future intelligence (in physical and computational terms, say).

Note that the qualitative leap reviewed above was not one that happened shortly after human ancestors diverged from chimp ancestors. Instead, it was a much more recent leap that has been unfolding gradually since the first humans appeared, and which has continued to accelerate in recent centuries, as we have developed ever more advanced science and mathematics. In other words, this qualitative step has been a product of cultural evolution just as much as biological evolution. Early humans presumably had a roughly similar potential to learn modern language, science, mathematics, and so on. But such conceptual tools could not be acquired in the absence of a surrounding culture able to teach these innovations.

Ramez Naam has made a similar point:

If there was ever a singularity in human history, it occurred when humans evolved complex symbolic reasoning, which enabled language and eventually mathematics and science. Homo sapiens before this point would have been totally incapable of understanding our lives today. We have a far greater ability to understand what might happen at some point 10 million years in the future than they would to understand what would happen a few tens of thousands of years in the future.

II. Cumulative Technological Innovation

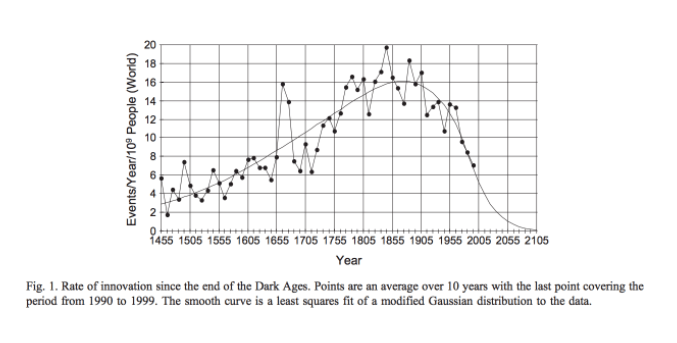

The second zero-to-one difference between humans and chimps is that we humans build things and refine our technology over time. To be sure, many non-human animals use tools in the form of sticks and stones, and some even shape primitive tools of their own. But only humans improve and build upon the technological inventions of their ancestors.

Thus, humans are unique in expanding their abilities by systematically exploiting their environment, molding the things around them into increasingly productive self-extensions. We have turned wildlands into crop fields, we have created technologies that can harvest energy, and we have built external memories far more reliable than our own, such as books and hard disks.

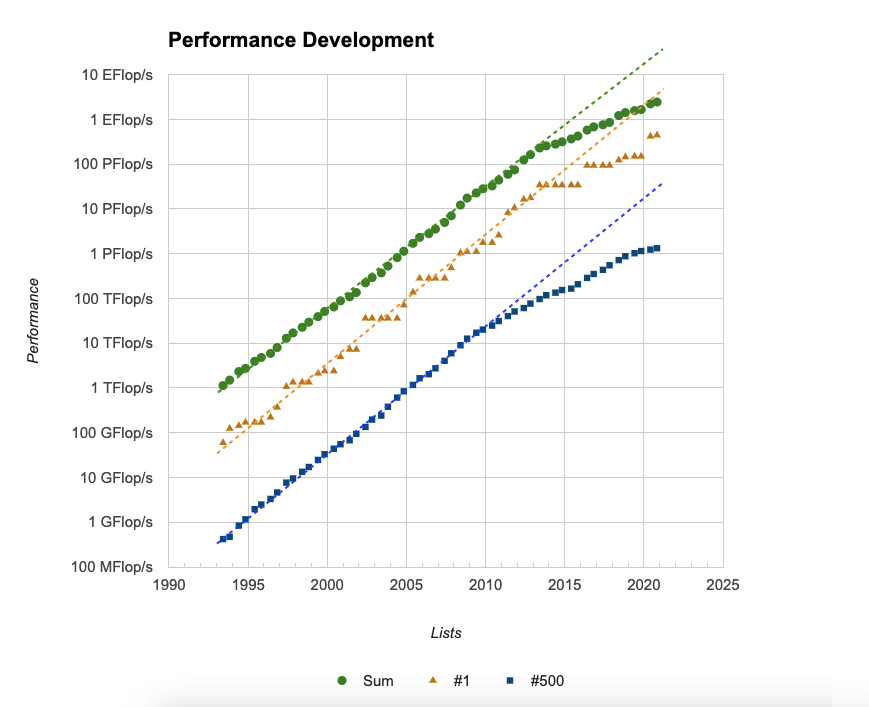

This is another qualitative leap that cannot be repeated: the step from having absolutely no cumulative technology to exploiting and optimizing our external environment toward our own ends — the step from having no external memory to having the current repository of stored human knowledge at our fingertips, and from harvesting absolutely no energy (other than through individual digestion) to collectively harvesting and using hundreds of quintillions of Joules every year.

Of course, it is possible to improve on and expand these innovations. We can harvest greater amounts of energy, for example, and create even larger external memories. Yet these are merely quantitative differences, and humanity indeed continually makes such improvements each year. They are not zero-to-one differences that only a new species could bring about.

In sum, we are unique in being the first species that systematically sculpted our surrounding environment and turned it into ever-improving tools. This step cannot be repeated, only expanded further.

Just like the qualitative leap in our symbolic reasoning skills, the qualitative leap in our ability to create technology and shape our environment emerged not between chimps and early humans, but between early humans and today’s humans, as the result of a cultural process occurring over thousands of years. In fact, the two leaps have been closely related: our ability to reason and communicate symbolically has enabled us to create cumulative technological innovation. Conversely, our technologies have allowed us to refine our knowledge and conceptual tools (e.g. via books, telescopes, and particle accelerators); and such improved knowledge has in turn made us able to build even better technologies with which we could advance our knowledge even further, and so on.

This, in a nutshell, is the story of the interdependent growth of human knowledge and technology, a story of recursive self-improvement (Simler, 2019, “On scientific networks”). It is not really a story about the individual human brain per se. After all, the human brain does not accomplish much in isolation. It is more a story about what happened between and around brains: in the exchange of information in networks of brains and in the external creations designed by them — a story made possible by the fact that the human brain is unique in being by far the most cultural brain of all, with its singular capacity to learn from and cooperate with others.

The Range of Human Abilities Is Surprisingly Wide

Another way in which an analogy to chimps is often drawn is by imagining an intelligence scale along which different species are ranked, such that, for example, we have “rats at 30, chimps at 60, the village idiot at 90, the average human at 98, and Einstein at 100”, and where future AI may in turn be ranked many hundreds of points higher than Einstein. According to this picture, it is not just that humans will stand in relation to AI the way chimps stand in relation to humans, but that AI will be far superior still. The human-chimp analogy is, on this view, a severe understatement of the difference between humans and future AI.

Such an intelligence scale may seem intuitively compelling, but how does it correspond to reality? One way to probe this question is to examine the range of human abilities in chess (as but one example that may provide some perspective; it obviously does not represent the full picture by any means).

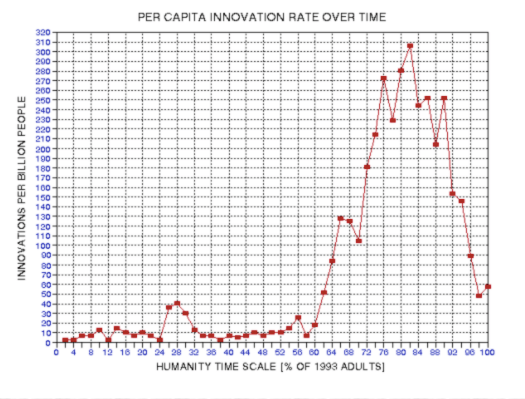

The standard way to rank chess skills is with the Elo rating system, which is a good predictor of the outcomes of chess games between different players, whether human, digital, or otherwise. An early human beginner will have a rating around 300, a novice around 800, and a rating in the range 2000-2199 is ranked as “Expert”. The highest rating ever achieved is 2882 by Magnus Carlsen.

How large is this range of chess skills in an absolute sense? Remarkably large, it turns out. For example, it took more than four decades from when computers were first able to beat a human chess novice (the 1950s), until a computer was able to beat the best human player (1997, officially). In other words, the span from novice to Kasparov corresponded to more than four decades of progress in both software and hardware, with the hardware progress amounting to a million times more computing power. This alone suggests that the human range of chess skills is rather wide.

Yet the range seems even broader when we consider the upper bounds of chess performance. After all, the fact that it took computers decades to go from human novice to world champion does not mean that the best human is not still far from the best a computer could be in theory. Surprisingly, however, this latter distance does in fact seem quite small. Estimates suggest that the best possible chess machine would have an Elo rating around 3600.

This would mean that the relative distance between the best possible computer and the best human is only around 700 Elo points (the Elo rating is essentially a measure of relative distance; 700 Elo points corresponds to a winning percentage of around 1.5 percent for the losing player).

Thus, the distance between the best human and a chess “Expert” appears similar to the distance between the best human and the best possible chess brain, while the distance between a human beginner and the best human is far greater (2500 Elo points). This stands in stark contrast to the intelligence scale outlined above, which would predict the complete opposite: the distance from a human novice to the best human should be comparatively small whereas the distance from the best human to the optimal brain should be the larger one by far.

Of course, chess is a limited game that by no means reflects all relevant tasks and abilities. Even so, the wide range of human abilities in chess still serves to question popular claims about the supposed narrowness of the human range of ability.

Why This Is Relevant

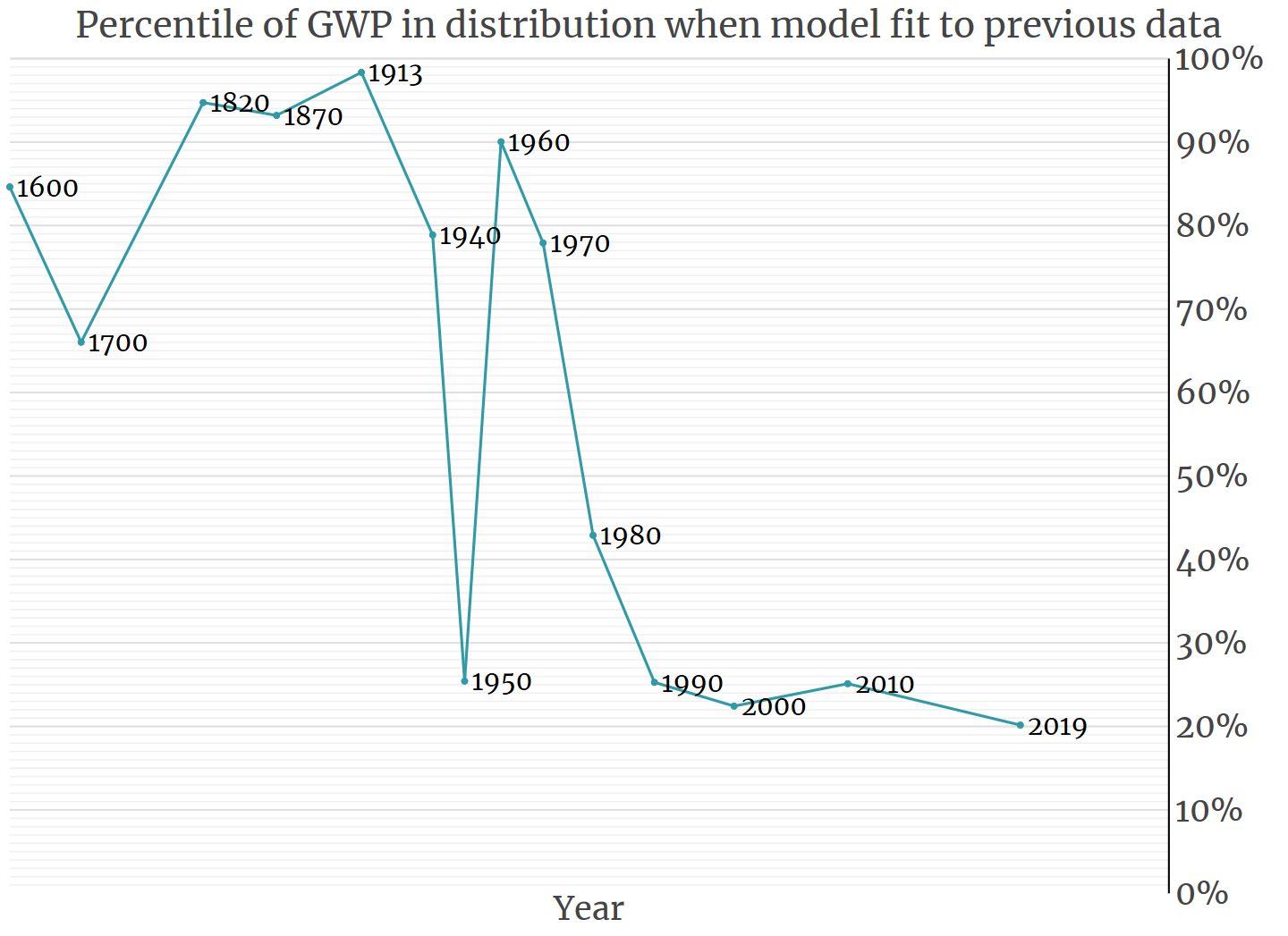

The errors of the human-chimp analogy are worth highlighting for a few reasons. First, the analogy may lead us to underestimate how much we currently know and are able to understand. To think that intelligent systems of the future will be as incomprehensible to us today as human affairs are to chimps is to underestimate how extensive and universal our current knowledge of the world in fact is — not just when it comes to physical and computational principles, but also in relation to general economic and game-theoretic principles. For example, we know a good deal about economic growth, and this knowledge has a lot to say about how we should expect future intelligent systems to grow. In particular, it suggests that a sudden local AI takeoff scenario (AI-FOOM growth) is unlikely.

The analogy can thus have an insidious influence by making us feel like current theories and trends cannot be trusted much, because look how different humans are from chimps, and look how puny the human brain is compared to ultimate limits. I think this is exactly the wrong way to think about the future. I believe we have good reasons to base our expectations on our best available theories and on a deep study of past trends, including the actual evolution of human competences — not on simple analogies.

Relatedly, the human-chimp analogy is also relevant in that it can lead us to greatly overestimate the probability of a localized AI takeoff scenario. That is, if we get the story about the evolution of human competences so wrong that we think the differences we observe today between chimps and humans reduce chiefly to a story about changes in individual brains — as opposed to a much broader story about biological, cultural, and technological developments — then we are likely to have similarly inaccurate expectations about what comparable “brain innovations” in some individual machine would lead to on their own.

If the human-chimp analogy causes us to overestimate the probability of a localized AI takeoff scenario, it may nudge us toward focusing too much on some single, concentrated future thing that we expect to be all-important: the AI that suddenly becomes qualitatively more competent than humans. In effect, the human-chimp analogy can lead us to neglect broader factors, such as cultural and institutional developments.

To be clear, the points above are by no means a case for complacency about risks from AI. It is important that we get a clear picture of such risks, and that we allocate our resources accordingly. But this requires us to rely on accurate models of the world. If we overemphasize one set of risks, we are by necessity underemphasizing others.