It is sometimes claimed that we cannot know whether suffering is ontologically prevalent — for example, we cannot rule out that suffering might exist in microorganisms such as bacteria, or even in the simplest physical processes. Relatedly, it has been argued that we cannot trust common-sense views and intuitions regarding the physical basis of suffering.

I agree with the spirit of these arguments, in that I think it is true that we cannot definitively rule out that suffering might exist in bacteria or fundamental physics, and I agree that we have good reasons to doubt common-sense intuitions about the nature of suffering. Nevertheless, I think discussions of expansive views of the ontological prevalence of suffering often present a somewhat unbalanced and, in my view, overly agnostic view of the physical basis of suffering. (By “expansive views”, I do not refer to views that hold that, say, insects are sentient, but rather views that hold that suffering exists in considerably simpler systems, such as in bacteria or fundamental physics.)

While we cannot definitively rule out that suffering might be ontologically prevalent, I do think that we have strong reasons to doubt it, as well as to doubt the practical importance of this possibility. My goal in this post is to present some of these reasons.

Contents

- Counterexamples: People who do not experience pain or suffering

- Our emerging understanding of pain and suffering

- Practical relevance

Counterexamples: People who do not experience pain or suffering

One argument against the notion that suffering is ontologically prevalent is that we seem to have counterexamples in people who do not experience pain or suffering. For example, various genetic conditions seemingly lead to a complete absence of pain and/or suffering. This, I submit, has significant implications for our views of the ontological prevalence (or non-prevalence) of suffering.

After all, the brains of these individuals include countless subatomic particles, basic biological processes, diverse instances of information processing, and so on, suggesting that none of these are in themselves sufficient to generate pain or suffering.

One might object that the brains of such people could be experiencing suffering — perhaps even intense suffering — that these people are just not able to consciously access. Yet even if we were to grant this claim, it does not change the basic argument that generic processes at the level of subatomic particles, basic biology, etc. do not seem sufficient to create suffering. For the processes that these people do consciously access presumably still entail at least some (indeed probably countless) subatomic particles, basic biological processes, electrochemical signals, different types of biological cells, diverse instances of information processing, and so on. This gives us reason to doubt all views that see suffering as an inherent or generic feature of processes at any of these (quite many) respective levels.

Of course, this argument is not limited to people who are congenitally unable to experience suffering; it applies to anyone who is just momentarily free from noticeable — let alone significant — pain or suffering. Any experiential moment that is free from significant suffering is meaningful evidence against highly expansive views of the ontological prevalence of significant suffering.

Our emerging understanding of pain and suffering

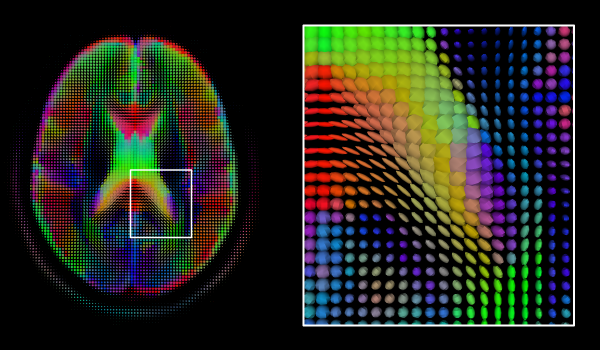

Another argument against expansive views of the prevalence of suffering is that our modern understanding of the biology of suffering gives us reason to doubt such views. That is, we have gained an increasingly refined understanding of the evolutionary, genetic, and neurobiological bases of pain and suffering, and the picture that emerges is that suffering is a complex phenomenon associated with specific genes and neural structures (as exemplified by the above-mentioned genetic conditions that knock out pain and/or suffering).

To be sure, the fact that suffering is associated with specific genes and neural structures in animals does not imply that suffering cannot be created in other ways in other systems. It does, however, suggest that suffering is unlikely to be found in simple systems that do not have remote analogues of these specific structures (since we otherwise should expect suffering to be associated with a much wider range structures and processes, not such an intricate and narrowly delineated set).

By analogy, consider the experience of wanting to go to a Taylor Swift concert so as to share the event with your Instagram followers. Do we have reason to believe that fundamental particles such as electrons, or microorganisms such as bacteria, might have such experiences? To go a step further, do we have reason to be agnostic as to whether electrons or bacteria might have such experiences?

These questions may seem too silly to merit contemplation. After all, we know that having a conscious desire to go to a concert for the purpose of online sharing requires rather advanced cognitive abilities that, at least in our case, are associated with extremely complex structures in the brain — not to mention that it requires an understanding of a larger cultural context that is far removed from the everyday concerns of electrons and bacteria. But the question is why we would see the case of suffering as being so different.

Of course, one might object that this is a bad analogy, since the experience described above is far more narrowly specified than is suffering as a general class of experience. I would agree that the experience described above is far more specific and unusual, but I still think the basic point of the analogy holds, in that our understanding is that suffering likewise rests on rather complex and specific structures (when it occurs in animal brains) — we might just not intuitively appreciate how complex and distinctive these structures are in the case of suffering, as opposed to in the Swift experience.

It seems inconsistent to allow ourselves to apply our deeper understanding of the Swift experience to strongly downgrade our credence in electron- or bacteria-level Swift experiences, while not allowing our deeper understanding of pain and suffering to strongly downgrade our credence in electron- or bacteria-level pain and suffering, even if the latter downgrade should be comparatively weaker (given the lower level of specificity of this broader class of experiences).

Practical relevance

It is worth stressing that, in the context of our priorities, the question is not whether we can rule out suffering in simple systems like electrons or bacteria. Rather, the question is whether the all-things-considered probability and weight of such hypothetical suffering is sufficiently large for it to merit any meaningful priority relative to other forms of suffering.

For example, one may hold a lexical view according to which no amount of putative “micro-discomfort” that we might ascribe to electrons or bacteria can ever be collectively worse than a single instance of extreme suffering. Likewise, even if one does not hold a strictly lexical view in theory, one might still hold that the probability of suffering in simple systems is so low that, relative to the expected prevalence of other kinds of suffering, it is so strongly dominated so as to merit practically no priority by comparison (cf. “Lexical priority to extreme suffering — in practice”).

After all, the risk of suffering in simple systems would not only have to be held up against the suffering of all currently existing animals on Earth, but also against the risk of worst-case outcomes that involve astronomical numbers of overtly tormented beings. In this broader perspective, it seems reasonable to believe that the risk of suffering in simple systems is massively dwarfed by the risk of such astronomical worst-case outcomes, partly because the latter risk seems considerably less speculative, and because it seems far more likely to involve the worst instances of suffering.

Relatedly, just as we should be open to considering the possibility of suffering in simple systems such as bacteria, it seems that we should also be open to the possibility that spending a lot of time contemplating this issue — and not least trying to raise concern for it — might be an enormous opportunity cost that will overall increase extreme suffering in the future (e.g. because it distracts people from more important issues, or because it pushes people toward dismissing suffering reducers as absurd or crazy).

To be clear, I am not saying that contemplating this issue in fact is such an opportunity cost. My point is simply that it is important not to treat highly speculative possibilities in a manner that is too one-sided, such that we make one speculative possibility disproportionately salient (e.g. there might be a lot of suffering in microorganisms or in fundamental physics), while neglecting to consider other speculative possibilities that may in some sense “balance out” the former (e.g. that prioritizing the risk of suffering in simple systems significantly increases extreme suffering).

In more general terms, it can be misleading to consider Pascallian wagers if we do not also consider their respective “counter-Pascallian” wagers. For example, what if believing in God actually overall increases the probability of you experiencing eternal suffering, such as by marginally increasing the probability that future people will create infinite universes that contain infinitely many versions of you that get tortured for life?

In this way, our view of Pascal’s wager may change drastically when we go beyond its original one-sided framing and consider a broader range of possibilities, and the same applies to Pascallian wagers relating to the purported suffering of simple entities like bacteria or electrons. When we consider a broader range of speculative hypotheses, it is hardly clear whether we should overall give more or less consideration to such simple entities than we currently do, at least when compared to how much consideration and priority we give to other forms of suffering.