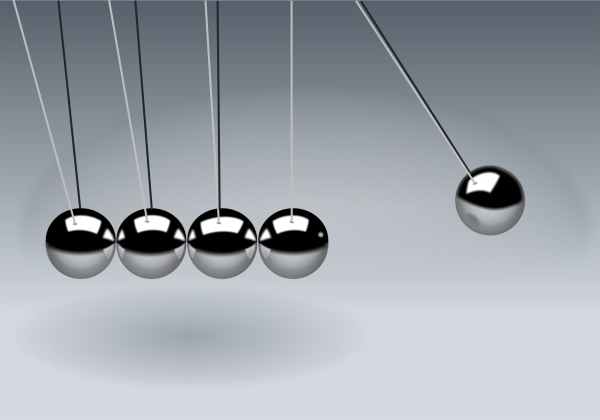

Two loose currents appear to be in opposition in today’s culture. One is animated by a strong insistence on empathy and compassion as core values, the other by a strong insistence on free speech as a core value. These two currents are often portrayed as though they must necessarily be in conflict. I think this is a mistake.

To be sure, the two values described above can be in tension, and none of them strictly imply the other. But it is possible to reconcile them in a refined and elegant synthesis. That, I submit, is what we should be aiming for. A synthesis of two vital and mutually reinforcing values.

Definitions and outline

It is crucial to distinguish 1) social and ethical norms, and 2) state-enforced laws. The argument I make here pertains to the first level. That is, I am arguing that we should aim to observe and promote ethical norms of compassion and open conversation, respectively.

What do I mean by these terms? Compassion is commonly defined as “sympathetic consciousness of others’ distress together with a desire to alleviate it”. I here use the term in a broader sense that also covers related virtues such as understanding, charitable interpretation, and kindness.

By norms of open conversation, or free expression, I mean norms that enable people to express their honest views openly, even when these views are controversial and uncomfortable. These norms do not entail that speech should be wholly unrestricted; after all, virtually everyone agrees that defamation and incitements to commit severe crimes should be illegal, as they commonly are.

My view is that we should roughly think of these two broad values as prima facie duties: we should generally strive to observe norms of compassion and open conversation, except in (rare) cases where other duties or virtues override these norms.

Below is a short defense of these two respective values, highlighting their importance in their own right. This is followed by a case that these values are not only compatible, but indeed strongly complementary. Finally, I explore what I see as some of the causes of our current state of polarization, and suggest five heuristics that might be useful going forward.

Brief defenses

Free speech

There are many strong arguments in favor of free speech. A famous collection of such arguments is On Liberty (1859) by John Stuart Mill, whose case for free speech is primarily based on the harm principle: the only reason power can legitimately be exercised over any individual against their will is to prevent harm to others.

This principle is intuitively compelling, although it leaves it unspecified what exactly counts as a harm to others. That is perhaps the main crux in discussions about free speech, and this alone could provide an argument in favor of free and open expression. For how can we clarify what should count as sufficient harm to others to justify the exercise of power if not through open discussion?

A necessary corrective to biased, fallible minds

Another important argument Mill makes in favor of free speech is based not merely on the rights of the speaker, but in equal part on the rights of the would-be listeners, who are also robbed by the suppression of free expression:

[T]he peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is, that it is robbing the human race; posterity as well as the existing generation; those who dissent from the opinion, still more than those who hold it. If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth: if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error.

In essence, Mill argues that, contrary to the annoyance we may instinctively feel, we should in fact be grateful for having our cherished views challenged, not least because it can help clarify and update our views.

Today, Mill’s argument can be further bolstered by a host of well-documented psychological biases. We now know that we are all vulnerable to confirmation bias, the bandwagon effect, groupthink, etc. These biases make it all too easy for us to deceive ourselves into thinking that we already possess the whole truth, although we most certainly do not. Consequently, if we want to hold reasonable beliefs, we should welcome and appreciate those who challenge the pitfalls of our groupish minds — pitfalls that we may otherwise be content to embrace.

After all, how can we know that our attempts to protect ourselves from hearing views that we dislike are not essentially unconscious attempts to protect our own confirmation bias? Free and open conversation is our best debiasing tool.

Strategic reasons

An altogether different argument in favor of honoring principles of free speech is that a failure to do so is strategically unwise. Indeed, as free-speech defender Noam Chomsky argues, there are several reasons to consider the suppression of free speech a tactical error if we are trying to create a better society.

First, reinforcing a norm of suppressing speech can have the unintended consequence of leading all sides, and perhaps eventually governments, to consider it increasingly legitimate to suppress certain forms of speech. “If they can suppress speech, why shouldn’t we?” The effects of such a regression would be worst for those who lack power.

Second, seeking to suppress speech is likely to backfire and to strengthen the other side, by making that side look more appealing than it in fact is — the suppressed becomes alluring — and by making the side that seeks to suppress speech look unreasonable, as though they are unable to muster a defense of their views.

When people try to make us do something, we tend to react negatively and to distance ourselves, even if we agreed with them from the outset (cf. psychological reactance). This is another strong reason against suppressing free expression, and against giving people the impression that they are not allowed to discuss or think certain things. It is human nature to react by asserting one’s freedom in defiance, even if it means voting for a president that one would otherwise have voted against. (See also Cialdini, 1984/2021, ch. 7.)

(Weak norms of free expression are thus a democratic problem in more than one way: it can keep citizens from voting in accordance with their ideal preferences both by making them ill-informed and by provoking votes of defiance.)

Steven Pinker has made a related point: if we place certain issues beyond the bounds of acceptable discourse, many people are likely to seek out discussion of these issues from unsavory sources, which can in turn put people on a path toward extreme and uncompassionate views. This parallels one of the main arguments made against the prevailing drug laws of today: such restrictions merely push the whole business into an underground market where people get dangerously polluted goods.

As Ayishat Akanbi eloquently put it (paraphrased slightly): if we suppress ideas, they will “operate with insidious undertones”, and we in effect “push people into the arms of extremism.”

Compassion

I will let my defense of compassion be even briefer still, as I have already made an elaborate defense of it in my book Suffering-Focused Ethics: Defense and Implications.

The short case is this: Suffering, especially the most intense suffering, truly matters. It is truly bad and truly worth preventing. Consequently, a desire to alleviate intense suffering is simply the most sensible response. Only a failure to connect with the reality of suffering can leave us apathetic. That is the simplest and foremost reason why compassion is of paramount importance.

Another reason to be compassionate, including in the broader sense of being kind and understanding, is that such an attitude has great instrumental benefits at the level of our communication and relations: it fosters trust and cooperation, which in turn enables win-win interactions.

However, to say that we should be compassionate is not to say that we should be game-theoretically naive in the sense of kindly allowing others to walk all over us. Compassion is wholly compatible with, and indeed mandates, tit for tat and assertiveness in the face of transgressions.

Lastly, it is worth emphasizing that compassion and empathy are not partisan values. Empathy is a human universal, and compassion has been considered a virtue in all major world traditions, as well as in most political movements, including political conservatism. Indeed, people of all political orientations score high on the harm/care dimension in Jonathan Haidt’s moral foundations framework. It really is a value on which people show uniquely wide agreement, at least on reflection. When they are not on Twitter.

Compassion and free speech: Complementary values

As noted above, the two values I defend here do not strictly imply each other, at least in some purely theoretical sense. But they are strongly complementary in many regards.

How free speech aids compassion

Compassion and the compassionate project can be aided by free speech in various ways. For example, to alleviate and prevent suffering effectively with our limited resources, we need to be able to discuss controversial ideas. We need to be able to discuss and measure different values and priorities against each other, including values that many people consider sacred and hence offensive to discuss.

As a case in point, in my book Suffering-Focused Ethics, I defend the moral primacy of reducing extreme suffering, even above other values that many people may consider sacred, and I further discuss the difficult question of which causes we should prioritize so as to best reduce extreme suffering. My arguments will no doubt be deeply offensive and infuriating to many, and I believe a substantial number of people would like to see my ideas suppressed if they could. This is not, of course, unique to my views: all treatises and positions on ethics are bound to be deemed too offensive and too dangerous by some.

This highlights the importance of free speech for ethics in general, and for the project of reducing suffering in particular. To conduct this most difficult conversation about what matters and what our priorities should be, we need a culture that allows, indeed promotes, this conversation — not a culture that stifles it. People who want to reduce suffering should thus have a strong interest in preserving and advancing free speech norms.

Another way in which free speech aids compassion is that, put simply, encouraging the free expression of, and listening to, each others’ underlying grievances can help us build mutual understanding, and in turn enable us to address our problems in cooperative ways. As Noam Chomsky notes in the context of hateful ideologies:

If you have a festering sore, the cure is not to irritate it, but to find out what its roots are and where it comes from, and to deal with those. Racist and other such speech is a festering sore. By silencing it, you simply amplify its appeal, and even lend it a veneer of respectability, as in fact we’ve seen very clearly in the last couple of years. And what has to be done, plainly, is to confront it, and to ask where it comes from, and to try to deal with the roots of such ideas. That’s the way to extirpate the ugliness and evil that lies behind such phenomena.

Human rights activist Deeyah Khan similarly argues that a root source of white supremacy is often a sense of fear and lack of opportunity, not inherent evil or apathy. She contends that the best solution to extremist ideologues is generally to engage in conversation and to seek to understand, not to shut down the conversation. (I recommend watching Khan’s documentary White Right: Meeting the Enemy.)

So while compassion per se does not directly imply free speech at some purely theoretical level, I would argue that a sophisticated and fully extrapolated version of compassion and the compassionate project does necessitate strong norms of free and open expression at the practical level.

How compassion aids free speech

One of the ways in which compassion can aid open conversation is exemplified in Deeyah Khan’s documentary mentioned above: she sits down and listens to white nationalists, seeking to understand them with compassion, which allows them to identify and express their own underlying issues, such as feelings of fear, vulnerability, and unworthiness. Such things can be difficult to share in apathetic and antagonistic environments, be they the macho ingroup or the angry outgroup. “Fuck you, racist” does not quite invite a response of “I’m afraid and hurting” as much as does, “How are you feeling, and what really motivates you?” On the contrary, it probably just serves to reinforce the facade of the pain.

We may not usually think of conditions that further the sharing of our underlying worries and vulnerabilities as a matter of free speech, perhaps because we all help perpetuate norms that suppress honesty about these things. But if free speech norms are essentially about enabling us to dare express our honest perspectives, then our de facto suppression of our inmost worries and vulnerabilities is indeed a free speech issue — and a rather consequential one at that (as I think Khan’s White Right makes clear). Compassion may well be the best remedy we have to our truth-subduing culture of suppressing our core worries and vulnerabilities.

A related way in which compassion, specifically the virtue of charitable interpretation, is important for free speech is, quite simply, that we suffocate free speech in its absence. If people hold back from expressing a nuanced view because they know that they will be strawmanned and vilely attacked based on bad-faith misinterpretations, then the state of free expression will be poor indeed.

In contrast, free expression will flourish when we do the opposite: when everyone engages with the strongest version of their opponents’ view — i.e. steelmans it — so that people feel positively motivated to present nuanced views and arguments in the expectation of being critiqued in good faith.

That, needless to say, is far from the state we are currently in.

Why we fail so spectacularly today

We are currently witnessing a primitive tribal dynamic exacerbated by the fact that we inhabit a treacherous environment to which we are not yet adapted, neither biologically nor culturally. I am speaking, of course, of the environment of screen-to-screen interaction.

Yet we should be clear that values and politics were never easy spheres to navigate in the first place. They have always been minefields. Politics is a notorious mind-killer for deep evolutionary reasons, and our political behavior is often more about signaling our group affiliations than it is about creating good policies. This is true not just of the “other side”; it is true of all of us, though we remain largely unaware of and self-deceived about it.

Thus, our predicament is that most of us care deeply about loyalty signaling, and such signaling has now become dangerously inflated. Moreover, we often use beliefs, ostensibly all about tracking reality, as ornaments that signal our group loyalty.

A hostage crisis instilling false assumptions

The two loose social currents I mentioned in the introduction can, I submit, be understood in this light. Specifically, values centered on empathy and compassion have become an ornament of sorts that signals loyalty to one side, while values centered on free speech have become a loyalty signal to another side. To be clear, I am not saying that these values are merely ornaments; they clearly are not. A value can be an ornament displayed with pride and be sincerely held at the same time. Yet our natural inclination to signal group loyalty can lead us to only express our support for one of these values, and to underemphasize the “opposing” value, even if we in fact do favor it.

In this way, the values of compassion and free speech have to some extent become hostages in a primitive tribal game, which in turn gives the false impression that there must be some deep conflict between these values, and that people must choose one or the other, as opposed to these values being, as I have argued, strongly complementary (with occasional and comparatively minor tensions).

The upshot is that supporters of free speech may feel nudged to display insensitivity in order to signal their loyalty and consistency, while supporters of anti-discrimination may feel nudged to oppose free speech.

Uncharitable claims beyond belief

A sad feature of this dynamic, and something that helps fuel it further, is how incredibly uncharitable the outer flanks of these two tribal currents are toward the other side.

“The PC-policing SJWs don’t care about the hard facts and just want to suppress them.”

“The free speech bros don’t care about minorities and just want to oppress them.”

To say that people are failing to steelman here would be quite the understatement. Indeed, this barely even qualifies as a strawman. It is more like the scream-man version of the other side: the worst, most scary version of the other side’s position that one could come up with. And this scream-man is repeatedly rehearsed in the partitioned echo halls of Twitter to the extent that people start believing these preposterously uncharitable narratives about the Scary Other.

It is a tragedy of the commons phenomenon: people are gleefully rewarded in their ingroup each time they promulgate the scream-man representation of the other side, and so it feels right to do so for individuals in these respective groups. But in the bigger picture, it just leaves everyone much worse off.

Distributions and the importance of self-criticism

To be sure, there are serious problems with significant numbers of people who conform too closely to the cartoon descriptions above. But a crucial point is that we must think in terms of statistical distributions. Specifically, the most loud-mouthed and scary two percent of the “other side” — a minority that tends to get a disproportionate amount of attention — should not be taken to represent everyone on that “side”, let alone its most reasonable representatives.

That being said, it is also true that many people on both sides tend to be bad at criticizing the harmful tendencies of their own “team”. There does indeed appear to be a tendency among certain defenders of free speech to fail to criticize and condemn those who discriminate against minorities. Likewise, there really does seem to be a tendency among certain progressives to fail to criticize and condemn those who suppress discussions of contentious issues.

This failure to speak out against the worst elements of one’s “own side” with sufficient force can create the false impression that most people on “our” side actually agree with these worst elements. That is how damning it is that we fail to criticize the transparent excesses of our ingroup in clear terms.

At cross-purposes

A problem with our failure to be charitable and to think in terms of distributions is that people end up talking past each other: both sides tend to criticize a strawman version of the other side based on the rabid tail-end elements of that side, which most people on the other side really do disagree with (although they may, as mentioned above, fail to express this disagreement with sufficient clarity).

This frequently results in debates with two sides that are in large part talking at cross-purposes: one side mostly defends free speech, while the other side mostly defends anti-discrimination, as though these were necessarily in great conflict. The failure to explore the compatibility and mutual complementarity of these values is striking.

The perils of screen-to-screen interaction

As noted above, our current mode of interaction only aggravates our political imbecility. When engaged in face-to-face interaction, we naturally relate to and empathize with the person before us, and we have a strong interest in keeping our interaction cordial so as to prevent it from escalating into conflict.

In screen-to-screen interaction, by contrast, our circuits for interpersonal interaction are all but inert, as we find ourselves shielded off from salient feedback and danger. Social media is road rage writ large. It is a road rage that renders it extra difficult to be charitable, and which renders it far more tempting to paint the outgroup in a bad light than it could ever be in a face-to-face environment, where preposterous strawmen would be called out and challenged in real time.

As a study on political polarization on Twitter put it:

Many messages contain sentiments more extreme than you would expect to encounter in face-to-face interactions, and the content is frequently disparaging of the identities and views associated with users across the partisan divide.

How can we reduce these unfortunate tendencies? The age of social media calls for new norms of communication.

Better norms for screen communication

Human culture has adapted to technological changes before, and it seems that we have no choice but to do the same today, in the face of our current state of cultural maladaptation. The following are five heuristics, or norms, that I think are likely to be useful in this regard.

1. The face-to-face heuristic

In light of the above, it seems sensible to adopt the precept of communicating online in roughly the same way we would communicate face-to-face. Our skills in face-to-face interaction have deep biological and cultural bases, and hence this heuristic is a cheap way to tap into a well-honed toolbox for functional human communication.

One effect of employing this heuristic will likely be a reduction of sarcastic and taunting comments. Such comments are rarely useful for taking our conversations to the next level, as we tend to realize face-to-face.

2. The nuance heuristic

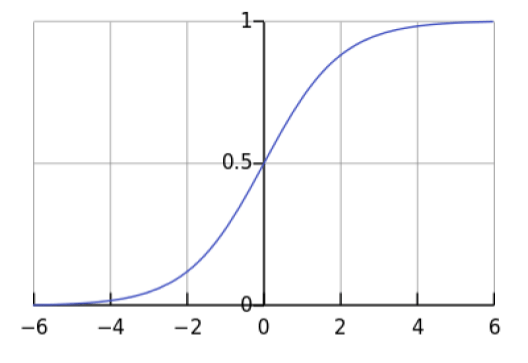

As I argue in my defense of nuance, much of the tension that we see today could likely be lessened greatly if we adopted more nuanced perspectives, such as by acknowledging grains of truth in different viewpoints, and by representing beliefs in terms of graded credences rather than posturing with overconfident all-or-nothing certainties.

3. The steelman heuristic

I have already mentioned this, but it can hardly be stressed enough: we must strive to be charitable and to steelman the views of our opponents, especially since our road-rage-behind-the-screen predicament makes it easier than ever to do the opposite.

Whenever we summarize and criticize the views of the other side, we should stop and ask ourselves: Is this really the most honest statement of their views that I can muster, let alone the strongest one? If I think their view is painfully stupid, do I really fully understand it? Do I really know what it entails and the best arguments that support it?

4. Compassion for the outgroup

As noted above, compassion really is a consensus value, if ever there were one. The disagreement mostly arises when it comes to which individuals we should extend our compassion to. Both of the notional “sides”, or social currents, described here suffer from selective compassion: they generally fail to show sufficient compassion and respect for the other side, which renders productive conversation difficult. And this point needs to be stressed with unique fervor today, as screens are an all too powerful and insidious catalyst for outgroup apathy.

5. Criticizing the ingroup

Condemning the excesses of one’s (vaguely associated) ingroup is also uniquely important today. Why? Because we now see large numbers of people behaving badly on social media, and our intuitions are statistically illiterate: we do not intuitively understand how a faction endorsing a certain view or behavior can simultaneously be large in number and constitute but a small minority of a given group. The world is big, and we mostly do not understand that (at an intuitive level).

Only by publicly countering the excesses of our “ingroup” can we make it clear to the other side — and perhaps also to our own side — that the extremists truly are a disapproved minority. Such ingroup criticism seems paramount if we are to mitigate the ongoing trend of polarization.

Conclusion

We have created a polarized online society in which people can feel pushed toward a needlessly narrow set of values — compassion or free speech, choose one! We are pushed in this way, not by totalitarian laws, but by modes of communication to which we are not yet adapted, and which we are navigating with patently defunct norms.

Norms are often more important than laws. After all, most of us can think of judgments from our peers that would be worse than a minor prison sentence. Hence, totalitarian laws are not required for free expression to be stifled into a de facto draconian state. The notion that harshly punitive norms do not restrict speech in costly ways is naive.

Sure, we should be free to judge others based on the things they say. But just how harshly should we judge people for discussing controversial views? And do we understand the risks and the strategic costs associated with such judgments, let alone the risks of trying to suppress certain viewpoints? If we place ourselves in opposition to free speech, and then give people the ultimatum of siding either with “us” or with “them”, a lot of people are going to choose the other side, even if that side has features they find genuinely worrying.

I have tried to argue that the choice between free speech or compassion is a false one. It really is possible to chart a balanced middle path of a free and compassionate society.