My aim in this post is to outline a variety of motivations that all point me in broadly the same direction: toward helping others in general and prioritizing the reduction of suffering in particular.

Contents

- Why list these motivations?

- Clarification

- Compassion

- Consistency

- Common sense: A trivial sacrifice compared to what others might gain

- The horror of extreme suffering: The “game over” motivation

- Personal identity: I am them

- Fairness

- Status and recognition

- Final reflections

Why list these motivations?

There are a few reasons why I consider it worthwhile to list this variety of moral motivations. For one, I happen to find it interesting to notice that my motivations for helping others are so diverse in their nature. (That might sound like a brag, but note that I am not saying that my motivations are necessarily all that flattering or unselfish.) This diversity in motivations is not obvious a priori, and it also seems different from how moral motivations are often described. For example, reasons to help others are frequently described in terms of a singular motivation, such as compassion.

Beyond mere interest, there may also be some psychological and altruistic benefits to identifying these motivations. For instance, if we realize that our commitment to helping others rests on a wide variety of motivations, this might in turn give us a greater sense that it is a robust commitment that we can be confident in, as opposed to being some brittle commitment that rests on just a single wobbly motivation.

Relatedly, if we have a sense of confidence in our altruistic commitment, and if we are aware that it rests on a broad set of motivations, this might also help strengthen and maintain this commitment. For example, one can speculate that it may be possible to tap into extra reserves of altruistic motivation by skillfully shifting between different sources of such motivation.

Another potential benefit of becoming more aware of, and drawing on, a greater variety of altruistic motivations is that they may each trigger different cognitive styles with their own unique benefits. For example, the patterns of thought and attention that are induced by compassion are likely different from those that are induced by a sense of rigorous impartiality, and these respective patterns might well complement each other.

Lastly, being aware of our altruistic motivations could help give us greater insight into our biases. For example, if we are strongly motivated by empathic concern, we might be biased toward mostly helping cute-looking beings who appeal to our empathy circuits, like kittens and squirrels, and toward downplaying the interests of beings who may look less cute, such as lizards and cockroaches. And note that such a bias can persist even if we are also motivated by impartiality at some level. Indeed, it is a recipe for bias to think that a mere cerebral endorsement of impartiality means that we will thereby adhere to impartiality at every level of our cognition. A better awareness of our moral motivations may help us avoid such naive mistakes.

Clarification

I should clarify that this post is not meant to capture everyone’s moral motivations, nor is my aim to convince people to embrace all the motivations I outline below. Rather, my intention is first and foremost to present the moral motivations that I myself am compelled by, and which all to some extent drive me to try to reduce suffering. That being said, I do suspect that many of these motivations will tend to resonate with others as well.

Compassion

Compassion has been defined as “sympathetic consciousness of others’ distress together with a desire to alleviate it”. This is similar to having empathic concern for others (compassion is often regarded as a component of empathic concern).

In contrast to some of the other motivations listed below, compassion is less cerebral and more directly felt as a motivation for helping others. For example, when we experience sympathy for someone’s misery, we hardly need to go through a sequence of inferences in order to be motivated to alleviate that misery. The motivation to help is almost baked into the sympathy itself. Indeed, studies suggest that empathic concern is a significant driver of costly altruism.

In my own case, I think compassion tends to play an important role, though I would not claim that it is sufficient or even necessary for motivating the general approach that I would endorse when it comes to helping others. One reason it is not sufficient is that it needs to be coupled with a more systematic component, which I would broadly refer to as ‘consistency’.

Consistency

As a motivation for helping others, consistency is rather different from compassion. For example, unlike compassion, consistency is cerebral in nature, to the degree that it almost has a logical or deductive character. That is, unlike compassion, consistency per se does not highlight others’ suffering or welfare from the outset. Instead, efforts to help others are more a consequence of applying consistency to our knowledge about our own direct experience: I know that intense suffering feels bad and is worth avoiding for me (all else equal), and hence, by consistency, I conclude that intense suffering feels bad and is worth avoiding for everyone (all else equal).

One might object that it is not inconsistent to view one’s own suffering as being different from the suffering of others, such as by arguing that there are relevant differences between one’s own suffering and the suffering of others. I think there are several points to discuss back and forth on this issue. However, I will not engage in such arguments here, since my aim in this section is not to defend consistency as a moral motivation, but simply to present a rough outline as to how consistency can motivate efforts to help others.

As noted above, a consistency-based motivation for helping others does not strictly require compassion. However, in psychological terms, since none of us are natural consistency-maximizers, it seems likely that compassion will usually be helpful for getting altruistic motivations off the ground in practice. Conversely, as hinted in the previous section, compassion alone is not sufficient for motivating the most effective actions for helping others. After all, one can have a strong desire to reduce suffering without having the consistency-based motivation to treat equal suffering equally and to spend one’s limited resources accordingly.

In short, the respective motivations of compassion and consistency seem to each have unique benefits that make them worth combining, and I would say that they are both core pillars in my own motivations for helping others.

Common sense: A trivial sacrifice compared to what others might gain

Another motivation that appeals to me might be described as a commonsense motivation. That is, there is a vast number of sentient beings in the world, of which I am just one, and hence the beneficial impact that I can have on other sentient beings is vastly greater than the beneficial impact I can have on my own life. After all, once my own basic needs are met, there is probably little I can do to improve my wellbeing further. Indeed, I will likely find it more meaningful and fulfilling to try to help others than to try to improve my own happiness (cf. the paradox of hedonism and the psychological benefits of having a prosocial purpose).

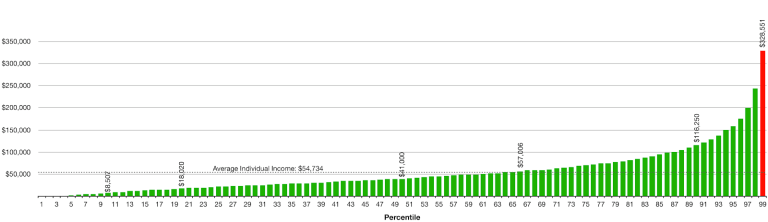

Of course, it is difficult to quantify just how much greater our impact on others might be compared to our impact on ourselves. Yet given the enormous number of sentient beings who exist around us, and given that our impact potentially reaches far into the future, it is not unreasonable to think that it could be greater by at least a factor of a million (e.g. we may prevent a million times as many instances of similarly bad suffering in expectation for others than for ourselves). Indeed, I think that a factor of around a billion is more plausible (again, in expectation, relative to the difference we can make for ourselves when our basic needs are already met).

In light of this massive difference in potential impact, it feels like a no-brainer to dedicate a significant amount of resources toward helping others, especially when my own basic needs are already met. Not doing so would amount to giving several orders of magnitude greater importance to my own wellbeing than to the wellbeing of others, and I see no justification for that. Indeed, one need not endorse anything close to perfect consistency and impartiality to believe that such a massively skewed valuation is implausible. It is arguably just common sense.

The horror of extreme suffering: The “game over” motivation

A particularly strong motivation for me is the sheer horror of extreme suffering. I refer to this as the “game over” motivation because that is my reaction when I witness cases of extreme suffering: a clear sense that nothing is more important than the prevention of such extreme horrors. Game over.

One might argue that this motivation is not distinct from compassion and empathic concern in the broadest sense. And I would agree that it is a species of that broad category of motivations. But I also think there is something distinctive about this “game over” motivation compared to generic empathic concern. For example, the “game over” motivation seems meaningfully different from the motivation to help someone who is struggling in more ordinary ways. In fact, I think there is a sense in which our common circuitry of sympathetic relating practically breaks down when it comes to extreme suffering. The suffering becomes so extreme and unthinkable that our “sympathometer” crashes, and we in effect check out. This is another reason it seems accurate to describe it as a “game over” motivation.

Where the motivations listed above all serve to motivate efforts to help others in general, the motivation described in this section is more of a driver as to what, specifically, I consider the highest priority when it comes to helping others, namely to alleviate and prevent extreme suffering.

Personal identity: I am them

Another motivation derives from what may be called a universal view of personal identity, also known as open individualism. This view entails that all sentient beings are essentially different versions of you, and that there is no deep sense in which the future consciousness-moments of your future self (in the usual narrow sense) is more ‘you’ than the future consciousness-moments of other beings.

Again, I will not try to defend this view here, as opposed to just describing how it can motivate efforts to help others (for a defense, see e.g. Kolak, 2004; Leighton, 2011, ch. 7; Vinding, 2017).

I happen to accept this view of personal identity, and in my opinion it ultimately leaves no alternative but to work for the benefit of all sentient beings. In light of open individualism, it makes no more sense to endorse narrow egoism than to, say, only care about one’s own suffering on Tuesdays. Both equally amount to an arbitrary disregard of my own suffering from an open individualist perspective.

This is one of the ways in which my motivations for helping others are not necessarily all that flattering: on a psychological level, I often feel that I am selfishly trying to prevent future versions of myself from being tortured, virtually none of whom will share my name.

I would say that the “I am them” motivation is generally a strong driver for me, not in a way that changes any of the basic upshots derived from the other motivations, but in a way that reinforces them.

Fairness

Considerations and intuitions related to fairness are also motivating to me. For example, I am lucky to have been born in a relatively wealthy country, and not least to have been born as a human rather than as a tightly confined chicken in a factory farm or a preyed-upon mouse in the wild. There is no sense in which I personally deserve this luck over those who are born in conditions of extreme misery and destitution. Consequently, it is only fair that I “pay back” my relative luck by working to help those beings who were or will be much less lucky in terms of their birth conditions and the like.

I should note that this is not among my stronger or more salient motivations, but I still think it has significant appeal and that it plays some role for me.

Status and recognition

Lastly, I want to highlight the motivation that any cynic would rightly emphasize, namely to gain status and recognition. Helping others can be a way to gain recognition and esteem among our peers, and I am obviously also motivated by that.

There is quite a taboo around acknowledging this motive, but I think that is a mistake. It is simply a fact about the human mind that we want recognition, and this is not necessarily a problem in and of itself. It only becomes a problem if we allow our drive for status to corrupt our efforts to help others, which is no doubt a real risk. Yet we hardly reduce that risk by pretending that we are unaffected by these drives. On the contrary, openly admitting our status motives probably gives us a better chance of mitigating their potentially corrupting influence.

Moreover, while our status drives can impede our altruistic efforts, we should not overlook the possibility that they might sometimes do the opposite, namely improve our efforts to help others.

How could that realistically happen? One way it might happen is by forcing us to seek out the assessments of informed people. That is, if our altruistic efforts are partly driven by a motive to impress relevant experts and evaluators of our work, we might be more motivated to consider and integrate a wider range of informed perspectives (compared to if we were not motivated to impress such evaluators).

Of course, this only works if we are indeed motivated to impress an informed audience, as opposed to just any audience that may be eager to throw recognition after us. Seeking the right audience to impress — those who are impressed by genuinely helpful contributions — might thus be key to making our status drives work in favor of our altruistic efforts rather than against them (cf. Hanson, 2010; 2018).

Another reason to believe that status drives can be helpful is that they have proven to be psychologically potent for human beings. Hence, if we could hypothetically rob a human brain of its status drives, we might well reduce its altruistic drives overall, even if other sources of altruistic motivation were kept intact. It might be tantamount to removing a critical part of an engine, or at least a part that adds a significant boost.

In terms of my own motivations, I would say that drives for status often do help motivate my altruistic efforts, whether I endorse my status drives or not. Yet it is difficult to estimate the strength and influence of these drives. After all, the status motive is regarded as unflattering, and hence there are reasons to think that my mind systematically downplays its influence. Moreover, like all of the motivations listed here, the status motive probably varies in strength depending on contextual factors, such as whether I am around other people or not; I suspect that it becomes weaker when I am more isolated, which in effect suggests a way to reduce my status drives when needed.

I should also note that I aspire to view my status drives with extreme suspicion. Despite my claims about how status drives could potentially be helpful, I think the default — if we do not make an intense effort to hone and properly direct our status drives — is that they distort our efforts to help others. And I think the endeavor of questioning our status drives tends to be extremely difficult, not least since status-seeking behavior can take myriad forms that do not look or feel like status-seeking behavior at all. It might just look like “conforming to the obviously reasonable views of my peers”, or like “pursuing this obscure and interesting idea that somehow feels very important”.

So a key question I try to ask myself is: am I really trying to help sentient beings, or am I mostly trying to raise my personal status? And I strive to look at my professed answers with skepticism. Fortunately, I feel that the “I am them” motivation can be a powerful tool in this regard. It essentially forces the selfish parts of my mind to ask: do I really want to gain status more than I want to prevent my future self from being tortured? If not, then I have strong reasons to try to reduce any torture-increasing inefficiencies that might be introduced by my status motives, and to try, if possible, to harness my status motives in the direction of reducing my future torment.

Final reflections

The motivations described above make up quite a complicated mix, from other-oriented compassion and fairness to what feels more like a self-oriented motivation aimed at sparing myself (in an expansive sense) from extreme suffering. I find it striking just how diverse these motivations are, and how they nonetheless — from so seemingly different starting points — can end up converging toward roughly the same goal: to reduce suffering for all sentient beings.

For me, this convergence makes the motivation to help others feel akin to a rope that is weaved from many complementary materials: even if one of the strings is occasionally weakened, the others can usually still hold the rope together.

But again, it is worth stressing that the drive for status is somewhat of an exception, in that it takes serious effort to make this drive converge toward aims that truly help other sentient beings. More generally, I think it is important to never be complacent about the potential for our status drives to corrupt our motivations to help others, even if we feel like we are driven by a strong and diverse set of altruistic motivations. Status drives are like the One Ring: powerful yet easily corrupting, and they are probably best viewed as such.